19th JULY 1947 MYANMAR ( BURMA ) MARTYRS DAY

Burmese Martyrs' Day

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Martyrs' Day အာဇာနည်နေ့ | |

|---|---|

| Observed by | Myanmar |

| Type | National holiday |

| Date | 19 July |

| Next time | 19 July 2015 |

| Frequency | annual |

Martyrs' Day (Burmese: အာဇာနည်နေ့, pronounced: [ʔàzànì nḛ]) is a Burmese national holiday observed on 19 July to commemorate Gen. Aung San and seven other leaders of the pre-independence interim government—Thakin Mya, Ba Cho, Abdul Razak, Ba Win, Mahn Ba Khaing, Sao San Tun and Ohn Maung—all of whom were assassinated on that day in 1947. It is customary for high-ranking government officials to visit the Martyrs' Mausoleum in Yangon in the morning of that day to pay respects.

Myoma U Than Kywe led the ceremony of the First Burmese Martyrs' Day on July 20, 1947 in Rangoon.[1]

Contents

[hide]History[edit]

On July 19, 1947, at approximately 10:37 a.m., BST, several of Burma's independence leaders were gunned down by a group of armed men in uniform while they were holding a cabinet meeting at the Secretariat in downtown Yangon. The assassinations were planned by a rival political group, and the leader and alleged mastermind of that group Galon U Saw, together with the perpetrators, were tried and convicted by a special tribunal presided by Kyaw Myint with two other Barristers-at-law, Aung Thar Gyaw and Si Bu. In a judgment given on 30 December 1947 the tribunal sentenced U Saw and a few others to death and the rest were given prison sentences. Appeals to the High Court of Burma by U Saw and his accomplices were rejected on 8 March 1948. In a judgment written by Supreme Court Justice E Maung (1898–1977) on 27 April 1948 the Supreme Court refused leave to appeal against the original judgment. (All the judgments of the tribunal, the High Court and the Supreme Court were written in English. The judgment of the tribunal can be read in "A Trial in Burma" by Dr Maung Maung (Martinus Njhoff, 1963) and the judgment of the High Court and Supreme Court can be read in the 1948 Burma Law Reports.)

The President of Burma Sao Shwe Thaik refused to pardon or commute the sentences of most of those who were sentenced to death, and U Saw was hanged inside Rangoon's Insein jail on 8 May 1948. A number of perpetrators met the same fate. Others, who had played relatively minor roles and were sentenced to various terms of imprisonment, also spent several years in prison.

The assassinated were:[2]

- Aung San, Prime Minister

- Ba Cho, Minister of Information

- Mahn Ba Khaing, Minister of Industry

- Ba Win, Minister of Trade

- Thakin Mya, Minister of Home Affairs

- Abdul Razak, Minister of Education and National Planning

- Sao San Tun, Minister of Hills Regions

- Ohn Maung, Deputy Minister of Transport

- Ko Htwe, Bodyguard of Razak

Tin Tut, Minister of Finance, was seriously wounded but survived. Many Burmese believe that the British had a hand in the assassination plot one way or another; two British officers were also arrested at the time and one of them charged and convicted for supplying an agent of U Saw with arms and munitions enough to equip a small army, a large part of which was recovered from a lake next to U Saw's house in the immediate aftermath of the shooting.[3]

Soon after the assassinations, Sir Hubert Rance, the British governor of Burma appointed U Nu to head an interim administration and when Burma became independent on 4 January 1948, Nu became the first Prime Minister of independent Burma. July 19 was designated a public holiday and to be known as Martyr's Day.

Commemorations[edit]

Poem for Martyr's Day[edit]

Aung San Zarni

Born on February 13 was he

Born in 1915, son of Lawyer U Hpa Of Natmauk, in Magwe District Mother's name was Daw Suu The year 1947 died he On July 19 everyone wept He is the cause of our Independence He is the father of this nation. The blessings he had given us, the words he had uttered ... How can we ever take those out of our minds ... |

|

See also[edit]

Aung San

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about Aung San. For his daughter, see Aung San Suu Kyi.

- In this Burmese name, Bogyoke is an honorific.

| General Aung San အောင်ဆန်း | |

|---|---|

| |

| Deputy Chairman of the Executive Council of Burma | |

| In office September 1946 – 19 July 1947 | |

| Preceded by | None |

| Succeeded by | U Nu (as Prime Minister) |

| President of the Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League | |

| In office January 1946 – 19 July 1947 | |

| Preceded by | None |

| War Minister of Burma | |

| In office 1 August 1943 – 27 March 1945 | |

| Preceded by | None |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Htein Lin 13 February 1915 Natmauk, Magwe, British Burma |

| Died | 19 July 1947 (aged 32) Rangoon, British Burma |

| Resting place | Martyrs' Mausoleum, Myanmar |

| Nationality | Myanmar |

| Political party | Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League Communist Party of Burma |

| Spouse(s) | Khin Kyi (m. 1942) |

| Relations | U Pha (father) Daw Suu (mother) Ba Win (brother) Sein Win (nephew) |

| Children | Aung San Oo Aung San Lin Aung San Suu Kyi |

| Alma mater | Rangoon University Yenangyaung High School |

| Occupation | Politician, Soldier |

| Religion | Theravada Buddhism |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Burma National Army Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League Communist Party of Burma |

| Rank | Major General (highest rank in military at that time) |

| History of Burma |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

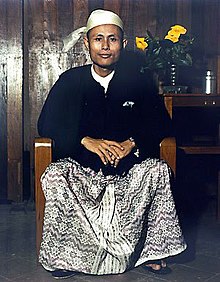

Bogyoke (General) Aung San (Burmese: ဗိုလ်ချုပ် အောင်ဆန်း; MLCTS: buil hkyup rki aung hcan:, pronounced: [bòdʑoʊʔ àʊɴ sʰáɴ]); 13 February 1915 – 19 July 1947) was a Burmese revolutionary, nationalist, founder of the modern Burmese army (Tatmadaw), and considered to be the Father of modern-day Burma. He was the founder of the Communist Party of Burma.

He was responsible for bringing Burma's independence from British colonial rule in Burma, but was assassinated six months before independence. He is recognized as the leading architect of independence, and the founder of the Union of Burma. Affectionately known as "Bogyoke" (General), Aung San is still widely admired by the Burmese people, and his name is still invoked in Burmese politics to this day.

Aung San had a daughter, Aung San Suu Kyi, who is a Burmese politician and the recipient of a Nobel Peace Prize.

Contents

[hide]Early life[edit]

Aung San was born to U Phar, a Myanmar-Chin lawyer, and his wife, Daw Suu, in Natmauk, Magway District, in central Burma on 13 February 1915. His family was already well known in the Burmese resistance movement; his grandfather Bo Min Yaung fought against the British annexation of Burma in 1886.

Aung San received his primary education at a Buddhist monastic school in Natmauk, and secondary education at Yenangyaung High School. He went to Rangoon University (now the University of Yangon).

Names of Aung San[edit]

- Name at birth: Htein Lin (ထိန်လင်း)

- As student leader and a thakin: Aung San (သခင်အောင်ဆန်း)

- Nom de guerre: Bo Teza (ဗိုလ်တေဇ)

- Japanese name: Omoda Monji (面田紋次)

- Chinese name: Tan Lu Sho

- Resistance period code name: Myo Aung (မျိုးအောင်), U Naung Cho (ဦးနောင်ချို)

- Contact code name with General Ne Win: Ko Set Pe (ကိုစက်ဖေ)

Struggle for independence[edit]

After Aung San entered Rangoon University in 1933, he quickly became a student leader.[1] He was elected to the executive committee of the Rangoon University Students' Union (RUSU). He then became editor of the RUSU's magazine Oway (Peacock's Call).[2]n

In February 1936, he was threatened with expulsion from the university, along with U Nu, for refusing to reveal the name of the author of the article Hell Hound at Large, which criticized a senior university official. This led to the Second University Students' Strike and the university authorities subsequently retracted the expulsions. In 1938, Aung San was elected president of both the Rangoon University Student Union (RUSU) and the All-Burma Students Union (ABSU), formed after the strike spread to Mandalay.[2][3] In the same year, the government appointed him as a student representative on the Rangoon University Act Amendment Committee.

In October 1938, Aung San left his law classes and entered national politics. At this point, he was anti-British and staunchly anti-imperialist. He became a Thakin (lord or master – a politically motivated title that proclaimed that the Burmese people were the true masters of their country, not the colonial rulers who had usurped the title for their exclusive use) when he joined the Dobama Asiayone (We Burmans Association). He acted as its general secretary until August 1940. While in this role, he helped organize a series of countrywide strikes that became known as ME 1300 Revolution (၁၃၀၀ ျပည့္ အေရးေတာ္ပံု, Htaung thoun ya byei ayeidawbon), based on the Burmese calendar year.

He also helped found another nationalist organization, the Freedom Bloc (ဗမာ့ထြက္ရပ္ဂိုဏ္း, Bama-htwet-yat Gaing), by forming an alliance between the Dobama, the ABSU, politically active monks and Dr Ba Maw'sSinyètha (Poor Man's) Party, and became its General Secretary. He also became a founder member and the first Secretary General of the Communist Party of Burma (CPB) in August 1939.[4] Shortly afterwards he co-founded the People's Revolutionary Party, renamed the Socialist Party after the Second World War.[2] In March 1940, he attended the Indian National Congress Assembly in Ramgarh, India. However, the government issued a warrant for his arrest due to Thakin attempts to organize a revolt against the British and he had to flee Burma.[3] He went first to China, seeking assistance from the nationalist government of the Kuomintang,[5]but he was intercepted by the Japanese military occupiers in Amoy, and was convinced by them to go to Japan instead.[2]

During the Second World War[edit]

Whilst Aung San was in Japan, the Blue Print for a Free Burma, which has been widely but mistakenly attributed to him, was drafted.[6] In February 1941, Aung San returned to Burma, with an offer of arms and financial support from the Fumimaro Konoe government of Japan. He returned briefly to Japan to receive more military training, along with the first batch of young revolutionaries who came to be known as the Thirty Comrades.[2]On 26 December 1941, with the help of the Minami Kikan, a secret intelligence unit that was formed to close the Burma Road and to support a national uprising and that was headed by Suzuki Keiji, he founded the Burma Independence Army (BIA) in Bangkok, Thailand.[2] It was aligned with Japan for most of World War II.[2]

The former capital of Burma, Rangoon (also known as Yangon), fell to the Japanese in March 1942 (as part of the Burma Campaign). The BIA formed an administration for the country under Thakin Tun Oke that operated in parallel with the Japanese military administration until the Japanese disbanded it. In July, the disbanded BIA was re-formed as the Burma Defense Army (BDA). Aung San was made a colonel and put in charge of the force.[3] He was later invited to Japan, and was presented with the Order of the Rising Sun by Emperor Hirohito.[3]

On 1 August 1943, the Japanese declared Burma an independent nation. Aung San was appointed War Minister, and the army was again renamed, this time as the Burma National Army (BNA).[3] Aung San soon became doubtful about Japanese promises of true independence and of Japan's ability to win the war. As William Slim, 1st Viscount Slim put it: "It was not long before Aung San found that what he meant by independence had little relation to what the Japanese were prepared to give - that he had exchanged an old master for an infinitely more tyrannical new one. As one of his leading followers once said to me, 'If the British sucked our blood, the Japanese ground our bones!' He became more and more disillusioned with the Japanese, and early in 1943 we got news from Seagrim, a most gallant officer who had remained in the Karen Hills at the ultimate cost of his life, that Aung San's feelings were changing. On 1 August 1944 he was bold enough to speak publicly with contempt of the Japanese brand of independence, and it was clear that, if they did not soon liquidate him, he might prove useful to us. ... At our first interview, Aung San began to take rather a high hand. ... I pointed out that he was in no position to take the line he had. I did not need his forces; I was destroying the Japanese quite nicely without their help, and could continue to do so. I would accept his help and that of his army only on the clear understanding that it implied no recognition of any provisional government. ... The British Government had announced its intention to grant self-government to Burma within the British Commonwealth, and we had better limit our discussion to the best method of throwing the Japanese out of the country ..."[7]

Aung San made plans to organize an uprising in Burma and made contact with the British authorities in India, in cooperation with the Communist leaders Thakin Than Tun andThakin Soe. On 27 March 1945, he led the BNA in a revolt against the Japanese occupiers and helped the Allies defeat the Japanese.[2] 27 March came to be commemorated as Resistance Day until the military regime renamed it 'Tatmadaw (Armed Forces) Day'.

After the War[edit]

After the return of the British, who established a military administration, the Anti-Fascist Organisation (AFO), formed in August 1944, was transformed into a united front, comprising the BNA, the Communists and the Socialists, and renamed the Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League (AFPFL). The Burma National Army was renamed the Patriotic Burmese Forces (PBF) and then gradually disarmed by the British as the Japanese were driven out of various parts of the country. The Patriotic Burmese Forces, while disbanded, were offered positions in the Burma Army under British command according to the Kandy conference agreement with Lord Louis Mountbatten in Ceylon in September 1945.[2] Aung San was offered the rank of Deputy Inspector General of the Burma Army, but he declined it in favor of becoming a civilian political leader and the military leader of the Pyithu yèbaw tat(People's Volunteer Organisation or PVO).[2]

In January 1946, Aung San became the President of the AFPFL following the return of civil government to Burma the previous October. In September, he was appointed Deputy Chairman of the Executive Council of Burma by the new British Governor Sir Hubert Rance, and was made responsible for defence and external affairs.[2] Rance and Mountbatten took a very different view from the former British Governor, Sir Reginald Dorman-Smith, and also Winston Churchill, who had called Aung San a 'traitor rebel leader'.[2] A rift had already developed inside the AFPFL between the Communists and Aung San, leading the nationalists and Socialists, which came to a head when Aung San and others accepted seats on the Executive Council. The rift culminated in the expulsion of Thakin Than Tun and the CPB from the AFPFL.[2][3]

Aung San was to all intents and purposes Prime Minister, although he was still subject to a British veto. On 27 January 1947, Aung San and the British Prime Minister Clement Attleesigned an agreement in London guaranteeing Burma's independence within a year; Aung San had been responsible for its negotiation.[2] At a press conference during a stopover inDelhi he stated that the Burmese wanted "complete independence" and not dominion status, and that they had "no inhibitions of any kind" about "contemplating a violent or non-violent struggle or both" in order to achieve it. He concluded that he hoped for the best, but was prepared for the worst.[3]

Two weeks after the signing of the agreement with Britain, Aung San signed an agreement at the Panglong Conference on 12 February 1947 with leaders from other national groups, expressing solidarity and support for a united Burma.[2][8] Karen representatives played a relatively minor role in the conference and, as subsequent rebellions revealed, remained alienated from the new state. U Aung Zan Wai, U Pe Khin, Major Aung, Sir Maung Gyi, Dr Sein Mya Maung and Myoma U Than Kywe were among the negotiators of the historic Panglong Conference negotiated with Aung San and other ethnic leaders in 1947. All these leaders unanimously decided to join the Union of Burma.

In the general election held in April 1947, the AFPFL won 176 out of the 210 seats in the Constituent Assembly, while the Karens won 24, the Communists 6 and Anglo-Burmans 4.[9] In July, Aung San convened a series of conferences at Sorrenta Villa in Rangoon to discuss the rehabilitation of Burma.

Assassination[edit]

On 19 July 1947, a gang of armed paramilitaries of former Prime Minister U Saw[10] broke into the Secretariat Building in downtown Rangoon during a meeting of the Executive Council (the shadow governmentestablished by the British in preparation for the transfer of power) and assassinated Aung San and six of his cabinet ministers, including his older brother Ba Win, father of Sein Win, leader of the government-in-exile, theNational Coalition Government of the Union of Burma (NCGUB). A cabinet secretary and a bodyguard were also killed. U Saw was subsequently tried and hanged.

Many mysteries still surround the assassination. There were rumours of a conspiracy involving the British—a variation on this theory was given new life in an influential, but sensationalist, documentary broadcast by theBBC on the 50th anniversary of the assassination in 1997. What did emerge in the course of the investigations at the time of the trial, however, was that several low-ranking British officers had sold guns to a number of Burmese politicians, including U Saw. Shortly after U Saw's conviction, Captain David Vivian, a British Army officer, was sentenced to five years imprisonment for supplying U Saw with weapons. Captain Vivian escaped from prison during the Karen uprising in Insein in early 1949. Little information about his motives was revealed during his trial or after the trial.[11]

Family[edit]

While he was War Minister in 1942, Aung San met and married Khin Kyi, and around the same time her sister met and married Thakin Than Tun, the Communist leader. Aung San and Khin Kyi had four children. Their youngest surviving child, Aung San Suu Kyi, is a Nobel Peace Prize laureate and leader of the Burmese Opposition, the National League for Democracy (NLD), and was until 13 November 2010 held under house arrest by themilitary regime. Their second son, Aung San Lin, died at age eight, when he drowned in an ornamental lake in the grounds of the house. The elder, Aung San Oo, is an engineer working in the United States and has disagreed with his sister's political activities. Their youngest daughter, Aung San Chit, born in September 1946, died on 26 September 1946, the same day Aung San got into Governor's Executive council, a few days after her birth.[12]Aung San's wife Daw Khin Kyi died on 27 December 1988.

Legacy[edit]

For his independence struggle and uniting the country as a single entity, he is revered as the Architect of Modern Burma and a national hero. His legacy assured his daughter's rise as a non-violence icon during the 8888 Uprising against military junta. A martyrs' mausoleum was built at the foot of the Shwedagon Pagoda and 19 July was designated Martyrs' Day (Azani nei), a public holiday. His literary work entitled "Burma's Challenge" was likewise popular.

Aung San's name had been invoked by successive Burmese governments since independence until the military regime in the 1990s tried to eradicate all traces of Aung San's memory. Nevertheless, several statues of him adorn the former capital Yangon and his portrait still has a place of pride in many homes and offices throughout the country. Scott Market, Yangon's most famous, was renamed Bogyoke Market in his memory, and Commissioner Road was retitled Bogyoke Aung San Road after independence. These names have been retained. Many towns and cities in Burma have thoroughfares and parks named after him. His portrait was held up everywhere during the 8888 Uprising in 1988 and used as a rallying point.[2] Following the 8888 Uprising, the government redesigned the national currency, the kyat, removing his picture and replacing it with scenes of Burmese life.

References[edit]

- ^ Maung Maung (1962). Aung San of Burma. The Hauge: Martinus Nijhoff for Yale University. pp. 22, 23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Martin Smith (1991). Burma – Insurgency and the Politics of Ethnicity. London and New Jersey: Zed Books. pp. 90, 54, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 65, 69, 66, 68, 62–63, 65, 77, 78, 6.

- ^ a b c d e f g Aung San Suu Kyi (1984). Aung San of Burma. Edinburgh: Kiscadale 1991. pp. 1, 10, 14, 17, 20, 22, 26, 27, 41, 44.

- ^ Lintner, Bertil (1990). The Rise and Fall of the Communist Party of Burma. Cornell Southeast Asias Program.

- ^ Stewart, Whitney. (1997). Aung San Suu Kyi: fearless voice of Burma. Twenty-First Century Books. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-8225-4931-4

- ^ Gustaaf Houtman, In Kei Nemoto (ed) – Reconsidering the Japanese military occupation in Burma (1942–45) (30 May 2007). "Aung San’s lan-zin, the Blue Print and the Japanese Occupation of Burma" (PDF). Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa (ILCAA), Tokyo: Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. pp. 179–227. ISBN 978-4-87297-9640.

- ^ Field Marshal Sir William Slim, Defeat into Victory, Cassell & Company, 2nd edition, 1956

- ^ "The Panglong Agreement, 1947". Online Burma/Myanmar Library.

- ^ Appleton, G. (1947). "Burma Two Years After Liberation". International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944–) (Blackwell Publishing) 23 (4): 510–521. JSTOR 3016561.

- ^ MAUNG ZARNI (19 July 2013). "Remembering the martyrs and their hopes for Burma". DVB NEWS. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ^ "Who Killed Aung San? - an interview with Gen. Kyaw Zaw". The Irrawaddy. August 1997. Retrieved 2006-11-04.

- ^ Wintle, Justin (2007). Perfect hostage: a life of Aung San Suu Kyi, Burma's prisoner of conscience. Skyhorse Publishing. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-60239-266-3.

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Aung San |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aung San. |

- Aung San's resolution to the Constituent Assembly regarding the Burmese Constitution, 16 June 1947

- Who really killed Aung San? Vol 1 on YouTube BBC documentary on YouTube, 19 July 1997

- Kin Oung. Eliminate the Elite - Assassination of Burma's General Aung San & his six cabinet colleagues. Uni of NSW Press. Special edition - Australia 2011

- http://www.bogyokeaungsanmovie.org/

| ||||||

|

In Burma, a Day for Fallen Heroes Is Resurrected

Children hold roses to be laid out at Aung San’s mausoleum in Rangoon on Martyrs’ Day. (Photo: JPaing / The Irrawaddy)

RANGOON—At a park here in Burma’s biggest city, a standing bronze statue of the country’s national hero, Gen Aung San, rarely draws visitors on ordinary days.

But on Friday, hundreds of young people gathered at the statue to honor the late general and his comrades—who were gunned down by a political rival exactly 66 years ago—in an act of commemoration that would have been prohibited before the country’s quasi-civilian government came to power in 2011.

One of Burma’s most important holidays, Martyrs’ Day, is marked each year on July 19, but such public displays of celebration were long forbidden by the country’s former military rulers, who sought to discredit Aung San—the father of democracy icon Aung San Suu Kyi—and his contribution to Burmese society.

“July 19 is the day we lost our leaders, and since then our country has experienced great suffering,” said Thurein, a Rangoon-based activist from Generation Wave, one of 30 youth networks gathered at the statue.

“We are here to take a lesson from what happened to them,” he added.

Martyrs’ Day was commemorated with a state-level ceremony for the first time last year, a practice that was repeated again this year with Vice President Dr Sai Mauk Kham and other high officials in attendance. The state-run New Light of Myanmar newspaper published an editorial on Friday entitled “Saluting Our Fallen Leaders,” while the front pages of other state-run dailies were filled with photographs of the fallen national heroes and an excerpt from Aung San’s 1947 speech to the public in Rangoon.

The annual holiday is a day for mourning in Burma, marking the anniversary of the assassination of Aung San and eight of his comrades in 1947, shortly before the country achieved independence from British rule the next year.

After the assassination, the Burmese government decreed that July 19 would become a national holiday, and for years thousands of Burmese would take the occasion to pay their respects at the fallen leaders’ mausoleum in Rangoon.

Following the 1988 popular uprising, the then-military junta downgraded the ceremony and declared that the mausoleum would be off-limits for ordinary people, fearing that a public gathering at the burial site would spark more unrest.

Thereafter, the only visible commemoration on July 19 was the state flag flying at half-mast. Children born after 1988 never heard a siren wail at 10:37 am, an old tradition to mark the exact time the leaders were assassinated.

But since reformist President Thein Sein took office two years ago, the decades-long Martyrs’ Day tradition seems to have been resurrected. The quasi-civilian government has also allowed some public tributes at the mausoleum, albeit with restrictions: No cell phones, cameras or bags of any kind were allowed at the site.

Since late morning on Friday, lines of people—including monks, schoolchildren and political party members—could be seen forming at the entrance of the mausoleum. When the clock struck 10:37, a siren blared from a public address system set up on the roof of a car near the park. Everyone in the vicinity bowed down for one minute in honor of the fallen leaders, while vehicles out on the roads honked their horns to mark the mournful moment.

A small number of people also gathered at the entrance of the Secretariat building, the site of the assassination, although they were not permitted to go inside.

Among the group was Yumon Kyaw, who said she and the others passed yellow and red roses to security guards at the door to put at a Buddhist shrine in a room inside where Aung San and his comrades were gunned down.

“We brought flowers here today, because our leaders died here,” she said.

Asia-Pacific

Profile: Aung San Suu Kyi

- 10 November 2014

- Asia-Pacific

Like the South African leader Nelson Mandela, Aung San Suu Kyi has become an international symbol of peaceful resistance in the face of oppression.

The 66-year-old spent most of the last two decades in some form of detention because of her efforts to bring democracy to military-ruled Myanmar (Burma).

In 1991, a year after her National League for Democracy (NLD) won an overwhelming victory in an election the junta later nullified, she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

The committee chairman called her "an outstanding example of the power of the powerless".

She was sidelined for Myanmar's first elections in two decades on 7 November 2010 but released from house arrest six days later.

As the new government embarked on a process of reform, Aung San Suu Kyi - known to many as "The Lady" - and her party rejoined the political process.

On 1 April 2012 she stood for parliament in a by-election, arguing it was what her supporters wanted even if the country's reforms were "not irreversible".

She and her fellow NLD candidates won a landslide victory and weeks later the former political prisoner was sworn into parliament, a move unimaginable before the 2010 polls.

However, she has since been frustrated with the pace of democratic development.

In November this year, she warned that Myanmar had not made any real reforms in the past two years and warned that the US - which dropped most of its sanctions against the country in 2012 - had been "overly optimistic" in the past.

She has also come in for criticism since her election by some rights groups for what they say has been a failure to speak up for Myanmar's minority groups during a time of ethnic violence in parts of the country.

Political pedigree

Aung San Suu Kyi is the daughter of Myanmar's independence hero, General Aung San.

He was assassinated during the transition period in July 1947, just six months before independence, when Ms Suu Kyi was only two.

In 1960 she went to India with her mother Daw Khin Kyi, who had been appointed Myanmar's ambassador to Delhi.

Four years later she went to Oxford University in the UK, where she studied philosophy, politics and economics. There she met her future husband, academic Michael Aris.

After stints of living and working in Japan and Bhutan, she settled in the UK to raise their two children, Alexander and Kim, but Burma was never far from her thoughts.

When she arrived back in Rangoon in 1988 - to look after her critically ill mother - Myanmar was in the midst of major political upheaval.

Thousands of students, office workers and monks took to the streets demanding democratic reform.

"I could not as my father's daughter remain indifferent to all that was going on," she said in a speech in Rangoon on 26 August 1988, and was propelled into leading the revolt against the then-dictator, General Ne Win.

Inspired by the non-violent campaigns of US civil rights leader Martin Luther King and India's Mahatma Gandhi, she organised rallies and travelled around the country, calling for peaceful democratic reform and free elections.

But the demonstrations were brutally suppressed by the army, who seized power in a coup on 18 September 1988.

The military government called national elections in May 1990 which Aung San Suu Kyi's NLD convincingly won, despite the fact that she herself was under house arrest and disqualified from standing.

But the junta refused to hand over control, and has remained in power ever since.

House arrest

Ms Suu Kyi remained under house arrest in Rangoon for six years, until she was released in July 1995.

She was again put under house arrest in September 2000, when she tried to travel to the city of Mandalay in defiance of travel restrictions.

She was released unconditionally in May 2002, but just over a year later she was put in prison following a clash between her supporters and a government-backed mob.

She was later allowed to return home - but again under effective house arrest.

During periods of confinement, Ms Suu Kyi busied herself studying and exercising. She meditated, worked on her French and Japanese language skills, and relaxed by playing Bach on the piano.

At times she was able to meet other NLD officials and selected diplomats.

But during her early years of detention, she was often in solitary confinement. She was not allowed to see her two sons or her husband, who died of cancer in March 1999.

The military authorities offered to allow her to travel to the UK to see him when he was gravely ill, but she felt compelled to refuse for fear she would not be allowed back into the country.

Her last period of house arrest ended in November 2010 and her son Kim Aris was allowed to visit her for the first time in a decade.

When by-elections were held in April 2012, to fill seats vacated by politicians who had taken government posts, she and her party contested seats, despite reservations.

"Some are a little bit too optimistic about the situation," she said in an interview before the vote. "We are cautiously optimistic. We are at the beginning of a road."

She and the NLD won 43 of the 45 seats contested, in an emphatic statement of support. Weeks later, Ms Suu Kyi took the oath in parliament and became the leader of the opposition.

And the following May, she embarked on a visit outside Myanmar for the first time in 24 years, in a sign of apparent confidence that its new leaders would allow her to return.

No comments:

Post a Comment