12th February 1928 Bardoli Satyagraha Led By Sardar Patel Had Drastically Affected The World Economy

Bardoli Satyagraha In Gujarat And World Economy Affected Drastically

* The peasant movements in U.P. and Malabar were thus closely linked with the politics at the national level. In UP., the impetus had come from the Home Rule Leagues and, later, from the Non-Cooperation and Khilafat movement. In Avadh, in the early months of 1921 when peasant activity was at its peak, it was difficult to distinguish between a Non cooperation meeting and a peasant rally. A similar situation arose in Malabar, where Khilafat and tenants’ meetings merged into one. But in both places, the recourse to violence by the peasants created a distance between them and the national movement and led to appeals by the nationalist leaders to the peasants that they should not indulge in violence. Often, the national leaders, especially Gandhiji, also asked the peasants to desist from taking extreme action like stopping the payment of rent to landlords.

This divergence between the actions and perceptions of peasants and local leaders and the understanding of the national leaders had often been interpreted as a sign of the fear of the middle class or bourgeois leadership that the movement would go out of its own ‘safe’ hands into that of supposedly more radical and militant leaders of the people. The call for restraint, both in the demands as well as in the methods used, is seen as proof of concern for the landlords and propertied classes of Indian society. It is possible, however, that the advice of the national leadership was prompted by the desire to protect the peasants from the consequences of violent revolt, consequences which did not remain hidden for long as both in U.P. and Malabar the Government launched heavy repression in order to crush the movements. Their advice that peasants should not push things too far with the landlords by refusing to pay rent could also stem from other considerations. The peasants themselves were not demanding abolition of rent or landlordism, they only wanted an end to ejectments, illegal levies, and exorbitant rents — demands which the national leadership supported. The recourse to extreme measures like refusal to pay rent was likely to push even the small landlords further into the lap of the government and destroy any chances of their maintaining a neutrality towards the on-going conflict between the government and the national movement.

* The no-tax movement that was launched in Bardoli taluq of Surat district in Gujarat in 1928 was also in many ways a child of the Non-cooperation days.’ Bardoli taluq had been selected in 1922 as the place from where Gandhiji would launch the civil disobedience campaign, but events in Chauri Chaura had changed all that and the campaign never took off. However, a marked change had taken place in the area because of the various preparations for the civil disobedience movement and the end result was that Bardoli had undergone a process of intense politicization and awareness of the political scene. The local leaders such as the brothers Kalyanji and Kunverji Mehta, and Dayalji Desai, had worked hard to spread the message of the Non-Cooperation Movement. These leaders, who had been working in the district as social reformers and political activists for at least a decade prior to Non-cooperation, had set up many national schools, persuaded students to leave government schools, carried out the boycott of foreign cloth and liquor, and had captured the Surat municipality.

After the withdrawal of the Non-Cooperation Movement, the Bardoli Congressmen had settled down to intense constructive work.

Stung by Gandhiji’s rebuke in 1922 that they had done nothing for the upliftment of the low-caste untouchable and tribal inhabitants — who were known by the name of Kaliparaj (dark people) to distinguish them from the high caste or Ujaliparaj (fair people) and who formed sixty per cent of the population of the taluq — these men, who belonged to high castes started work among the Kaliparaj through a network of six ashrams that were spread out over the taluq. These ashrams, many of which survive to this day as living institutions working for the education of the tribals, did much to lift the taluq out of the demoralization that had followed the withdrawal of 1922. Kunverji Mehta and Keshavji Ganeshji learnt the tribal dialect, and developed a ‘Kaliparaj literature’ with the assistance of the educated members of the Kaliparaj community, which contained poems and prose that aroused the Kaliparaj against the Hali system under which they laboured as hereditary labourers for upper-caste landowners, and exhorted them to abjure intoxicating drinks and high marriage expenses which led to financial ruin. Bhajan mandalis consisting of Kaliparaj and Ujaliparaj members were used to spread the message. Night schools were started to educate the Kaliparaj and in 1927 a school for the education of Kaliparaj children was set up in Bardoli town. Ashram workers had to often tce the hostility of upper-caste landowners who feared that all this would ‘spoil’ their labour. Annual Kallparaj conferences were held in 1922 and, in 1927, Gandhiji, who presided over the annual conference, initiated an enquiry into the conditions of the Kaliparaj , who he also now renamed as Raniparaf or the inhabitants of the forest in preference to the derogatory term Kaliparaj or dark people. Many leading figures of Gujarat including Narhari Parikh and Jugatram Dave conducted the inquiry which turned into a severe indictment of the Hall system, exploitation by money lenders and sexual exploitation of women by upper-castes. As a result of this, the Congress had built up a considerable’ base among the Kaliparaj, and could count on their support in the future.

Simultaneously, of course, the Ashram workers had continued to work among the landowning peasants as well, and had to an extent regained their influence among them. Therefore, when in January 1926 it became known that Jayakar, the officer charged with the duty of reassessment of the land revenue demand of the taluq, had recommended a thirty percent increase over the existing assessment, the Congress leaders were quick to protest against the increase and set up the Bardoli Inquiry Committee to go into the issue. Its report, published in July 1926, came to the conclusion that the increase was unjustified. This was followed by a campaign in the Press, the lead being taken by Young India and Navjivan edited by Gandhiji. The constitutionalist leaders of the area, including the members of the Legislative Council, also took up the issue. In July 1927, the Government reduced the enhancement to 21.97 per cent. But the concessions were too meagre and came too late to satisfy anybody. The constitutionalist leaders now began to advise the peasants to resist by paying only the current amount and withholding the enhanced amount. The ‘Ashram’ group, on the other hand, argued that the entire amount must be withheld if it was to have any effect on the Government. However, at this stage, the peasants seemed more inclined to heed the advice of the moderate leaders.

Gradually, however, as the limitations of the constitutional leadership became more apparent, and their unwillingness to lead even a movement based on the refusal of the enhanced amount was clear, the peasants began to move towards the ‘Ashram’ group of Congress leaders. The latter, on their pan had in the meanwhile contacted Vallabhbhai Patel and were persuading him to take on the leadership of the movement A meeting of representatives of sixty villages at Bamni in Kadod division formally invited Vallabhbhai to lead the campaign. The local leaders also met Gandhiji and after having assured him that the peasants were fully aware of the implications of such a campaign, secured his approval.

Patel reached Bardoli on 4 February and immediately had a series of meetings with the representatives of the peasants and the constitutionalist leaders. At one such meeting, the moderate leaders frankly told the audience that their methods had failed and they should now try Vallabhbhai’s methods. Vallabhbhai explained to the peasants the consequences of their proposed plan of action and advised them to give the matter a week’s thought. He then returned to Ahmedabad and wrote a letter to the Governor of Bombay explaining the miscalculations in the settlement report and requesting him to appoint an independent enquiry; else, he wrote, he would have to advise the peasants to refuse to pay the Land revenue and suffer the consequences.

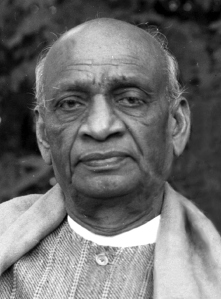

On 12 February, Patel returned to Bardoli and explained the situation, including the Government’s curt reply, to the peasants’ representatives, following this, a meeting of the occupants of Bardoli taluq passed a resolution advising all occupants of land to refuse payment of the revised assessment until the Government appointed an independent tribunal or accepted the current amount as full payment. Peasants were asked to take oaths in the name of Prabhu (the Hindu name for god) and Khuda (the Muslim name for god) that they would not pay the land revenue. The resolution was followed by the recitation of sacred texts from the Gita and the Koran and songs from Kabir, who symbolized Hindu-Muslim unity. The Satyagraha had begun. Vallabhbhai Paid was ideally suited for leading the campaign. A veteran of the Kheda Satyagraha, the Nagpur Flag Satyagraha, and the Borsad Punitive Tax Satyagraha, he had emerged as a leader of Gujarat who was second only to Gandhiji. His capacities as an organizer, speaker, indefatigable campaigner, inspirer of ordinary men and women were already known, but it was the women of Bardoli who gave him the title of Sardar. The residents of Bardoli to this day recall the stirring effect of the Sardar’s speeches which he delivered in an idiom and style that was close to the peasant’s heart.

The Sardar divided the taluq into thirteen workers’ camps or Chhavanis each under the charge of an experienced leader. One hundred political workers drawn from all over the province, assisted by 1,500 volunteers, many of whom were students, formed the army of the movement. A publications bureau that brought out the daily Bardoli Satyagraha Patrika was set up. This Patrika contained reports about the movement, speeches of the leaders, pictures of the jabti or confiscation proceedings and other news. An army of volunteers distributed this to the farthest corners of the taluq. The movement also had its own intelligence wing, whose job was to find out who the indecisive peasants were. The members of the intelligence wing would shadow them night and day to see that they did not pay their dues, secure information about Government moves, especially of the likelihood of jabti (confiscation) and then warn the villagers to lock up their houses or flee to neighbouring Baroda.

The main mobilization was done through extensive propaganda via meetings, speeches, pamphlets, and door to door persuasion. Special emphasis was placed on the mobilization of women and many women activists like Mithuben Petit, a Parsi lady from Bombay, Bhaktiba, the wife of Darbar Gopaldas, Maniben Patel, the Sardar’ s daughter, Shardaben Shah and Sharda Mehta were recruited for the purpose. As a result, women often outnumbered men at the meetings and stood firm in their resolve not to submit to Government threats. Students were another special target and they were asked to persuade their families to remain thin.

Those who showed signs of weakness were brought into line by means of social pressure and threats of social boycott. Caste and village panchayats were used effectively for this purpose and those who opposed the movement had to face the prospect of being refused essential services from sweepers, barbers, washermen, agricultural labourers, and of being socially boycotted by their kinsmen and neighbours. These threats were usually sufficient to prevent any weakening. Government officials faced the worst of this form of pressure. They were refused supplies, services, transport and found it almost impossible to carry out their official duties. The work that the Congress leaders had done among the Kaliparaj people also paid dividends during this movement and the Government was totally unsuccessful in its attempts to use them against the upper caste peasants.

Sardar Patel and his colleagues also made constant efforts to see that they carried the constitutionalist and moderate leadership, as well as public opinion, with them on all important issues. The result of this was that very soon the Government found even its supporters and sympathizers, as well as impartial men, deserting its side. Many members of the Bombay Legislative Council like K.M. Munshi and Laiji Naranji, the representatives of the Indian Merchants Chamber, who were not hot-headed extremists, resigned their seats. By July 1928, the Viceroy, Lord Irwin, himself began to doubt the correctness of the Bombay Government’s stand and put pressure on Governor Wilson to find a way out. Uncomfortable questions had started appearing in the British Parliament as well.

Public opinion in the country was getting more and more restive and anti-Government. Peasants in many parts of Bombay Presidency were threatening to agitate for revision of the revenue assessments in their areas. Workers in Bombay textile mills were on strike and there was a threat that Patel and the Bombay Communists would combine in bringing about a railway strike that would make movement of troops and supplies to Bardoli impossible. The Bombay Youth League and other organizations had mobilized the people of Bombay for huge public meetings and demonstrations. Punjab was offering to send jathas on foot to Bardoli. Gandhiji had shifted to Bardoli on 2 August, 1928, in order to take over the reins of the movement if Patel was arrested. All told, a retreat, if it could be covered up by a face saving device, seemed the best way out for the Government.

The face-saving device was provided by the Legislative Council members from Surat who wrote a letter to the Governor assuring him that his pre-condition for an enquiry would be satisfied. The letter contained no reference to what the pre-condition was (though everyone knew that it was full payment of the enhanced rent) because an understanding had already been reached that the full enhanced rent would not be paid. Nobody took the Governor seriously when he declared that he had secured an ‘unconditional surrender.” It was the Bardoli peasants who had won.

The enquiry, conducted by a judicial officer, Broomfield, and a revenue officer, Maxwell, came to the conclusion that the increase had been unjustified, and reduced the enhancement to 6.03 per cent. The New statesman of London summed up the whole affair on 5 May 1929: ‘The report of the Committee constitutes the worst rebuff which any local government in India has received for many years and may have far- reaching results… It would be difficult to find an incident quite comparable with this in the long and controversial annals of Indian Land Revenue. ‘

The relationship of Bardoli and other peasant struggles with the struggle for freedom can best be described in Gandhiji’s pithy words: ‘Whatever the Bardoli struggle may be, it clearly is not a struggle for the direct attainment of Swaraj. That every such awakening, every such effort as that of Bardoli will bring Swaraj nearer and may bring it nearer even than any direct effort is undoubtedly true.’

Bardoli Satyagraha

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Bardoli Satyagraha of 1928, in the state of Gujarat, India during the period of the British Raj, was a major episode ofcivil disobedience and revolt in the Indian Independence Movement. The movement was eventually led by Vallabhbhai Patel, and its success gave rise to Patel becoming one of the main leaders of the independence movement.

Contents

[hide]Background[edit]

Mahatma Gandhi had led two great revolts of communities of poor Indian farmers against the tyranny of the British government and allied landlords in Champaran, Bihar, and Kheda, Gujarat. Success in both struggles had helped win the farmers economic and civil rights, and electrified India's people.

In 1920, the Indian National Congress under Gandhi's leadership launched the Non-Cooperation Movement. Millions of Indians revolted against the British, boycotting the courts, government services, schools and disavowing titles, pensions and British clothes and goods. The freedom fighters, known as Satyagrahis, peacefully protested authoritarian British laws, and called for India's independence. Many thousands were beaten, tortured and arrested.

In 1922, however, a mob of protestors killed some policemen in Chauri Chaura. Fearing a slide into violence and anarchy, Gandhi called for the struggle to be suspended. He was arrested in the same year and sentenced to be imprisoned for six years, but released in 1924. In this struggle, many considered Sardar Patel as the Lord of Bardoli.

The crisis[edit]

In 1925, the taluka of Bardoli in Gujarat suffered from floods and famine, causing crop production to suffer and leaving farmers facing great financial troubles. However, the government of the Bombay Presidency had raised the tax rate by 30% that year, and despite petitions from civic groups, refused to cancel the rise in the face of the calamities. The situation for the farmers was grave enough that they barely had enough property and crops to pay off the tax, let alone for feeding themselves afterwards.

Considering the options[edit]

The Gujarati activists Narhari Parikh, Ravi Shankar Vyas, and Mohanlal Pandya talked to village chieftains and farmers, and solicited the help of Gujarat's most prominent freedom fighter, Vallabhbhai Patel. Patel had previously guided Gujarat's farmers during the Kheda struggle, and had served recently as Ahmedabad's municipal president. He was widely respected by common Gujaratis across the state.

Patel told a delegation of farmers frankly that if they should realize fully what a revolt would imply. He would not lead them unless he had the unanimous understanding and agreement of all the villages involved. Refusing payment of taxes could lead to their property being confiscated, including their lands, and many would go to jail. They could face complete decimation. The villagers replied that they were prepared for the worst, but definitely could not accept the government's injustice.

Patel then asked Gandhi to consider the matter. But Gandhi merely asked what Patel thought, and when the latter replied with confidence about the prospects, he gave his blessing. But Gandhi and Patel agreed that neither the Congress nor Gandhi would directly involve themselves, and the struggle left entirely to the people of Bardoli taluka.

The struggle[edit]

See also: Satyagraha

Patel first wrote to the Governor of Bombay, asking him to reduce the taxes for the year in face of the calamities. But the Governor ignored the letter, and reciprocated by announcing the date of collection.

Patel then instructed all the farmers of Bardoli taluka to refuse payment of their taxes. Aided by Parikh, Vyas and Pandya, he divided Bardoli into several zones – each with a leader and volunteers specifically assigned. Patel also placed some Gujarati activists close to the government, to act as informers on the movements of government officials.

Above all, Patel instructed the farmers to remain completely non-violent, and not respond physically to any incitements or aggressive actions from officials. He reassured them that the struggle would not end until not only the cancellation of all taxes for the year, but also when all the seized property and lands were returned to their rightful owners.

The farmers received complete support from their compatriots in Gujarat. Many hid their most precious belongings with relatives in other parts, and the protestors received financial support and essential supplies from supporters in other parts. But Patel refused permission to enthusiastic supporters in Gujarat and other parts of India from going on sympathetic protest.

The Government declared that it would crush the revolt. Along with tax inspectors, bands of Pathans were gathered from northwest India to forcibly seize the property of the villagers and terrorize them. The Pathans and the men of the collectors forced themselves into the houses and took all property, including cattle (resisters had begun keeping their cattle inside their locked homes when the collectors were about, in order to prevent them from seizing the animals from the fields).[1]

The government began to auction the houses and the lands. But not a single man from Gujarat or anywhere else in India came forward to buy them. Patel had appointed volunteers in every village to keep watch. As soon as he sighted the officials who were coming to auction the property, the volunteer would sound his bugle. The farmers would leave the village and hide in the jungles. The officials would find the entire village empty.[2] They could never find out who owned a particular house.

However, some rich people from Bombay came to buy some lands. There was also one village recorded that paid the tax. A complete social boycott was organized against them, wherein relatives broke their ties to families in the village. Other ways social boycott was enforced against landowners who broke with the tax strike or purchased seized land were to refuse to rent their fields or to work as laborers for them.[3]

Members of the legislative councils of Bombay and across India were angered by the terrible treatment of the protesting farmers. Indian members resigned their offices, and expressed open support of the farmers.[4] The Government was heavily criticized, even by many in the Raj's offices.

Resolution[edit]

In 1928, an agreement was finally brokered by a Parsi member of the Bombay government. The Government agreed to restore the confiscated lands and properties, as well as cancel revenue payment not only for the year, but cancel the 30% raise until after the succeeding year.

The farmers celebrated their victory, but Patel continued to work to ensure that all lands and properties were returned to every farmer, and that no one was left out. When the Government refused to ask the people who had bought some of the lands to return them, wealthy sympathizers from Bombay bought them out, and returned the lands to the rightful owners.

Commemoration[edit]

The momentum from the Bardoli victory aided in the resurrection of the freedom struggle nationwide.[5] In 1930, the Congress would declare Indian independence, and the Salt Satyagraha would be launched by Gandhi.

While Patel credited Gandhi's teachings and the farmers' undying resolve, people across the nation recognized his vital leadership. It was women of bardoli who bestowed the title Sardar for the first time, which in Gujarati and most Indian languages means Chief or Leader. It was after Bardoli that Sardar Patel became one of India's most important leaders.

See also[edit]

- Non-Cooperation Movement

- Champaran and Kheda Satyagraha

- Farmers' movements in India

- Patel: A Life, Rajmohan Gandhi

References[edit]

- Jump up^ Gross, David M. (2014). 99 Tactics of Successful Tax Resistance Campaigns. Picket Line Press. pp. 97–98. ISBN 978-1490572741.

- Jump up^ Gross, David M. (2014). 99 Tactics of Successful Tax Resistance Campaigns. Picket Line Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-1490572741.

- Jump up^ Gross, David M. (2014). 99 Tactics of Successful Tax Resistance Campaigns. Picket Line Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-1490572741.

- Jump up^ Gross, David M. (2014). 99 Tactics of Successful Tax Resistance Campaigns. Picket Line Press. pp. 167–68. ISBN 978-1490572741.

- Jump up^ Gross, David M. (2014). 99 Tactics of Successful Tax Resistance Campaigns. Picket Line Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-1490572741.

External links[edit]

| |||

| ||

| ||

No comments:

Post a Comment