10th February 1691 Job Charnock Established The First English Factory At Cacutta (Now Kolkata) West Bengal India

Job Charnock

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Jobe Charnock | |

|---|---|

| Born | c. 1630 London, England |

| Died | 10 January 1692 Calcutta(now Kolkata), India |

| Occupation | Colonial administrator |

| Known for | Executive worker of east India company |

Jobe Charnock (c. 1630–1692) was a servant and administrator of theEnglish East India Company and was celebrated as the founder of the city of Calcutta now Kolkata. In 2003 the Kolkata High Court announced that although Charnock was a major contributor to its development, that villages existed on the site of Calcutta well before Charnock's time.[1][2][3]

Contents

[hide]Early life and career[edit]

Charnock came from a Lancashire family and was the second son of Richard Charnock of London. Stephen Charnock (1628–1680) was probably his elder brother. He was part of a private trading enterprise in the employ of the merchant Maurice Thomson between 1650 and 1653, but in January 1658 he joined the East India Company's service in Bengal, where he was stationed at Cossimbazar, Hooghly

Charnock was described as a silent morose man, not popular among his contemporaries, but as "always a faithful man to the Company", which rated his services very highly.[4] In addition to his business acumen, he won the Company's esteem by stamping out smuggling among his less scrupulous colleagues. His zeal in this regard made him enemies who throughout his life spread malicious gossip to discredit him.[5]

Patna factory[edit]

Charnock was entrusted with the duty of procuring the Company's saltpetre and appointed to the centre of the trade,Patna in Bihar, on 2 February 1659. After four years at the factory he contemplated returning to England, but the court of directors in London were keen to retain his services, and won him over by promoting him to the position of chief factor in 1664.

About 1663 Charnock took a Hindu widow as his common-law wife. A Company servant, Alexander Hamilton, later wrote that she had been a sati and that Charnock, smitten by her beauty, had rescued her from her husband's funeral pyre by the Ganges in Bihar.[6][7] She was said to be a fifteen-year-old Rajput princess.[8] Charnock renamed her Maria, and soon after he was accused of converting to Hinduism.[9] Though he remained a devout Christian,[10] the story of his conversion and moral laxity was so widely believed that it became a cautionary tale in a more puritanical age.[11]

Charnock was promoted to the rank of senior merchant by 1666, and became third in the Bengal hierarchy in 1676. He was now the Company's longest-serving servant in Bengal, and applied for a transfer to a more senior post. After some haggling due to difficulties with resentful colleagues who hoped to see him sent away to Madras, on 3 January 1679 the directors promoted him to the position of head at Cossimbazar, second in charge of the Company's operations in Bengal.

Rivalry with William Hedges[edit]

Cossimbazar was notorious as a smugglers' den, and when Charnock assumed his new post on Christmas Day 1680 it was over the objections of Streynsham Master, president at Madras, who oversaw the Company's operations in the wholebay of Bengal. Master received a reprimand from the directors for his interference, but although they agreed to free Bengal from oversight by the Madras presidency, Charnock's hopes of promotion to the top Bengal post at Hooghly were dashed when in 1681 the directors sent out one of their own, William Hedges, as agent of the bay and governor of Bengal.

On Hedges's arrival at Hooghly Charnock found him to be an officious neophyte. The rivalry between the Company's two most senior servants in Bengal was aggravated by the intrigues of Company servants and interlopers keen to undermine Charnock's authority and resume their smuggling operations on the side. Charnock was further irritated by the fact that members of Hedges's staff from Hooghly were regularly sabotaging their colleagues' work in Cossimbazar by poaching the local commodities. In 1684 the exasperated directors restored supervisory control over Bengal to the new president at Madras, William Gyfford, and replaced Hedges in Bengal with John Beard, the elder.

Chief agent in Bengal[edit]

When Beard died on 28 August 1685 Charnock finally assumed the position of agent and chief in the bay of Bengal.[12] By this time a crisis had arisen over restrictions on trade, and in particular the Mughal nawab's imposition of a customs duty of 3½ per cent, which the English refused to pay on the grounds that it was in breach of the original firman which exempted them from customs.[13] Relations with the nawab deteriorated into violent conflict. When Charnock received word of his promotion Cossimbazar was under siege, and he could not leave to take up his responsibilities at Hooghly until April 1686. On his arrival he continued to resist what he saw as extortion, by force or persuasion, and when these did not serve, by taking the Company's business elsewhere.

Finding himself again besieged at Hooghly, Charnock put the Company's goods and servants on board his light vessels. Pursued by the nawab's troops, on 20 December 1686 he dropped down the river 27 miles (43 km) to Sutanuti, then "a low swampy village of scattered huts",[14] but a place well chosen for the purpose of defence.[15] From Sutanuti he moved on to Hijili in February 1687, where he was again besieged from March to June 1687. After negotiating a truce and safe passage, he transferred the factory back to Sutanuti in November 1687.

Captain Nicolson was the first British colonialist to invade Hijli and captured the port only. Afterwards, in 1687, Job Charnock, with 400 soldiers, captured Hijli, defeating Hindu and Mughal Emperors. A war broke out with the Mughal Empire, and a treaty was signed between Job Charnock and the Mughul Emperor. The loss [almost crushed by the Mughals/Mughal Emperor] suffered by Job Charnock, forced him to leave Hijli and proceed towards Uluberia while the Mughal Emperor continued to rule the kingdom. From there they finally settled at Sutanuti, and slowly established Calcutta (which is currently known as Kolkata) for their business in eastern India. This was the start of East India Company in India.

It was probably during this interlude at Sutanuti that Charnock suffered an irreparable personal loss in the death of his wife Maria. They had been together for some twenty-five years. They had one son (who would predecease his father), and three surviving daughters who were later baptised in Madras. Although Maria was buried like a Christian, and not cremated as a Hindu,[16] Charnock was said to sacrifice a cock over her grave each year on the anniversary of her death, "after the Pagan Manner".[17] The ritual resembles the Sufi custom of the panch peer or "five saints", which Charnock might have learnt from his years in Bihar.[18] He was also said to have built his garden house at Barrackpore so as to be near her grave.[19]

Chittagong expedition[edit]

By 1686 the secret committee of the court of directors in London had decided the Company should establish a fortified settlement in Bengal, to resist what they regarded as arbitrary exactions and violent harassment by Mughal officials:

Accordingly in September 1688 the largest naval force the Company had ever assembled swept into the bay, with orders to blockade the ports and arrest the ships of the Grand Mughal, and, if this did not bring satisfaction, to take the town of Chittagong. Beard being dead, authority devolved to a reluctant Charnock as commander-in-chief. As he anticipated, Chittagong proved remote and unviable. Sutanuti had in the meantime been razed by the nawab's troops, therefore the squadron sailed for Madras, arriving on 7 March 1689.

Calcutta[edit]

In Madras Charnock persuaded the reluctant council, over the objections of its president, his old opponent William Hedges, that Sutanuti was the best place to establish the headquarters in Bengal, because of its defensible position and its deep-water anchorage for the fleet. The selection of the future capital of India was entirely due to his stubborn resolution.[21]

In March 1690 the Company received permission from Aurangzeb in Delhi to re-establish a factory in Bengal, and on 24 August 1690 Charnock returned to set up his headquarters in the place he called Calcutta; the appointment of a new nawab ensured this agreement was honoured, and on 10 February 1691 an imperial grant was issued for the English to "contentedly continue their trade".[22][23]

The directors showed their approval of Charnock's initiative by making his agency independent of Madras on 22 January 1692. Thereafter "Calcutta grew steadily till it became India's 'city of cities' and capital".[24]

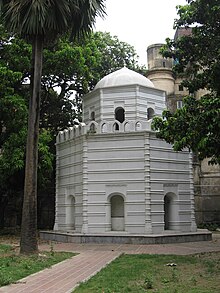

Mausoleum[edit]

Charnock died in Calcutta on 10 January 1692 (or 1693 according to an exhibition at the Victoria Memorial which points out that the 1692 date on his gravestone refers to an old calendar system by which the new year began in March), shortly after the death of his son. His three surviving daughters all remained in Calcutta: Mary (d. 19 February 1697), Elizabeth (d. August 1753), and Katherine (d. 21 January 1701); all found wealthy English husbands.[25] Mary married the first president of Bengal, Sir Charles Eyre.

A mausoleum was erected over Charnock's simple grave by Eyre, his son-in-law and successor, in 1695. It can still be seen in the graveyard of St. John's Church, the second oldest Protestant church in Calcutta after John Zacharias Kiernander's Old Mission Church (1770), and is now regarded as a national monument.[26][27] His tomb is made from a kind of rock named after him as Charnockite.[28] It is inscribed with the Latin epitaph:

Translation:

The inscription omits any mention of Charnock's Hindu wife Maria. Eyre may have hoped to make the public image of his predecessors and in-laws seem more respectable to the growing Anglican community in Calcutta.[31] Even so, the monument was built by Bengali craftsmen, and its incorporation of Indo-Islamic design reflects the intersection of two cultures their union personified.[32]

Assessment[edit]

In the verdict of Sir Henry Yule:

Controversy[edit]

Main article: History of Kolkata

A Calcutta High Court ruling (16 May 2003)[34] based on a report from an academic committee, found that a 'highly civilised society' and 'an important trading centre' had existed on the site of Calcutta long before the first European settlers came down the Hooghly. They also found the place then called Kalikatah was an important religious centre due to the existence of the Kali temple in the adjacent village of Kalighat. The first literary reference to the site is found in Bipradas Pipilai's magnum opus Manasa Mangala which dates back to 1495. Abul Fazl's Ain-I-Akbari dating 1596 also mentions the place. The Sabarna Roy Choudhury family was granted the Jagirdari of Kalikatah by Emperor Jehangir in 1608. The report added that Charnock's name was just the first of those, including Eyre, Goldsborough, Lakshmikanta Majumdar, the Sett Bysack families and Sabarna Choudhuries, that could be celebrated for developing the city.[35] The court declared that Charnock ought not to be regarded as the founder of Calcutta, and ordered government authorities to purge his name from all text books and official documents containing the history of the founding story of the city.[36]

Other historical authorities reject such revisionism:

Notes[edit]

- ^ Thankappan Nair, Job Charnock: The Founder of Calcutta, Calcutta: Engineering Press, 1977

- ^ Banglapedia Article on Job Charnock

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica article on Charnock

- ^ 3 January 1694, Diary of William Hedges, 2.293.

- ^ I. B. Watson, ‘Charnock, Job (c.1630–1693)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004; online edn, Jan 2008, accessed 29 August 2008.

- ^ Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies (1727), ed. William Foster, 2 vols (London: Argonaut, 1930), Vol. II, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Thankappan Nair, Job Charnock: The Founder of Calcutta, Calcutta: Engineering Press, 1977.

- ^ Francis Jarman, 'Sati: From exotic custom to relativist controversy', CultureScan, Vol. 2, No. 5 (December 2002), p. 8.

- ^ De Almeida 228.

- ^ I. B. Watson, ‘Charnock, Job (c.1630–1693)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004; online edn, Jan 2008, accessed 29 August 2008.

- ^ 'The Englishman in India', The Times (25 October 1867), pg. 4, col. E.

- ^ 'The Imperial Gazetteer of India', The Times (26 May 1881), pg. 5, col. C.

- ^ 'The Early History of the English in Bengal', The Times (31 August 1889), pg. 11 col. D.

- ^ Bhabani Bhattacharya, 'City of Cities is now callous', The Times (26 January 1962), xxi.

- ^ Bhabani Roy Choudhury, Bangiya Sabarna Katha Kalishetra Kalikatah, Manna Publication. ISBN 81-87648-36-8.

- ^ Grant, 'Origin and Progress of English Connexion with India', Calcutta Review, No. XIII, Vol. VII (January–June 1847), p. 260.

- ^ Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies (1727), ed. William Foster, 2 vols (London: Argonaut, 1930), Vol. II, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Prabodh Biswas, 'Job Charnock', in Sukanta Chaudhuri (ed.), Calcutta: The Living City, Vol. I: The Past (Calcutta: 1990), pp. 6–7.

- ^ Grant, 'Origin and Progress of English Connexion with India', Calcutta Review, No. XIII, Vol. VII (January–June 1847), p. 260.

- ^ 'The Early History of the English in Bengal', The Times (31 August 1889), pg. 11 col. D.

- ^ 'Charnock, Job', Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed. (1911), vol. 5, p. 947.

- ^ Charles Robert Wilson, ed., The Early Annals of the English in Bengal, 2 vols. in 3 pts (1895–1911), vol. 1: The Diary of William Hedges (1681–1687), ed. R. Barlow and H. Yule, 3 vols., Hakluyt Society, 74–5, 78 (1887–89).

- ^ I. B. Watson, ‘Charnock, Job (c.1630–1693)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004; online edn, Jan 2008, accessed 29 August 2008.

- ^ Bhabani Bhattacharya, 'City of Cities is now callous', The Times (26 January 1962), xxi.

- ^ Francis Jarman, 'Sati: From exotic custom to relativist controversy', CultureScan, Vol. 2, No. 5 (December 2002), p. 8.

- ^ 'St. John's, Calcutta,' The Times (20 September 1955), pg. 10, col. E.

- ^ Forgotten founder lies unsung

- ^ Job Charnock's memorial in Calcutta

- ^ The Bengal Obituary: or, A Record to Perpetuate the Memory of Departed Worth to Which Is Added Biographical Sketches and Memoirs of History of British India, since the Formation of the European Settlement to the Present Time (1848), ed. P. Thankappan Nair (Calcutta: 1991), p. 2.

- ^ Robert Travers, 'Death and the Nabob: Imperialism and Commemoration in Eighteenth-Century India', Past and Present, No. 196 (August 2007), pp. 89–90, fn. 18

- ^ H. B. Hyde, 'Notes on the Mausoleum of Job Charnock and the Bones Recently Discovered within It', Proceedings of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Vol. XXIX (March 1893), pp. 79–80.

- ^ Robert Travers, 'Death and the Nabob: Imperialism and Commemoration in Eighteenth-Century India', Past and Present, No. 196 (August 2007), p. 92.

- ^ 'The Early History of the English in Bengal', The Times, (31 August 1889), pg. 11, col. E.

- ^ Gupta, Subhrangshu (17 May 2003). "Job Charnock not Kolkata founder: HC Says city has no foundation day". The Tribuneonline edition. Retrieved 17 December 2006.

- ^ Job Charnock not Kolkata's Founder: Expert committee, Times of India (31 January 2003). Accessed 1 September 2008.

- ^ Bangiya Sabarna Katha Kalishetra Kalikatah by Bhabani Roy Choudhury, Manna Publication. ISBN 81-87648-36-8

- ^ I. B. Watson, ‘Charnock, Job (c.1630–1693)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004; online edn, Jan 2008, accessed 20 Aug 2008.

References[edit]

- Da Almeida, Hermione. Indian Renaissance: British Romantic Art And the Prospect of India

- H.E. Busteed Echoes from Old Calcutta (Calcutta) 1908

- Bangiya Sabarna Katha Kalishetra Kalikatah by Bhabani Roy Choudhury, Manna Publication. ISBN 81-87648-36-8

- Unknown (1829), Historical and Ecclesiastical Sketches of Bengal; From the Earliest Settlement, Until the Virtual Conquest of that Country by the English, in 1757, Read Online

- Bruce (1810), Annals of the Honorable East-India Company: from their establishment by the charter of queen Elizabeth, 1600 to the Union of the London and the English East India Companies 1707-8, Vol-I, Read Online

- Bruce (1810), Annals of the Honorable East-India Company: from their establishment by the charter of queen Elizabeth, 1600 to the Union of the London and the English East India Companies 1707-8, Vol-II, Read Online

- Marshman, John Clark (1867), The History of India From the Earliest Period to the Close of Lord Dalhousie's Administration – 1867, Vol-I, Read Online

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Job Charnock. |

- Banglapedia

- Encyclopedia article on Charnock

- Charnock's article at the website of William Carey University

- Job Charnock: Banglapedia

- [1] Official Website of Sabarna Roy Choudhury Paribar Parishad

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911).Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911).Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

| ||

Categories:

- People associated with the British East India Company

- English businesspeople

- History of Kolkata

- 17th-century English people

- 1630s births

- 1693 deaths

- People from London

- City founders

Ads related to: job charnock established the first english factory at calcutta

Related Searches

Web Results

Afterwards, in 1687, Job Charnock, ... and slowly established Calcutta ... Job Charnock, English knight and recentlythe most worthy agent of the English in this ...Calcutta, Job Charnock and the St John's Church - Free download as PDF File (.pdf), Text file (.txt) ... Also attached a map of Calcutta in 1756.The first "factory" ... This is the first time English soldiers came on the soil of Bengal. ... Job Charnock thought thatthe name of the place is Calcutta .Led by Job Charnock, an English merchant, the established a factory at ... the first strains ... at Kolkata wasestablished in the year of 1998 ...This particular page is not really a photo gallery per se. Rather, it intends to introduce Job Charnock and the origin ofthe City of Calcutta.Job Charnock was a servant and administrator of the English East India Company, traditionally regarded as thefounder of the city of Calcutta. ... establish a factory ...... Job Charnock was one of the first English traders to set foot in Calcutta ... and established it as a ... JobCharnock, English knight and ...... exactly on the site of charred ruins of an old factory, ... Job Charnock, the founder of Calcutta, ... the first Capital of British India was born.The English factory at Patna was ... Thus settled the earliest of the English settlers of Kolkata, ... Job Charnockwas probably one of the few Englishmen who ...Job Charnock placed the English interests upon ... Now the foundation of Calcutta as a fortified factory of the ... theEast India Company had to take ...Ads

No comments:

Post a Comment