24th SEPTEMBER 1859 NANASAHEB - DHUNDU PANT SEPOY MUTINY WARRIOR SENT IN EXILE NEPAL

The Great Rebellion (1857)

In 1793, the Empire’s rulers had imposed a `Permanent Settlement’ on India which privatised the land and dispossessed the peasants. The Empire took 50-60% of the peasants’ income in tax, more than the Mughal Emperors had taken, forcing the peasants into debt and then to sell their land to the bunyahs, the moneylenders. India’s wealth was pillaged and her agriculture starved, in order to rack profit and rent up. The profits went to British investors, the rents to the Empire’s allies, the landlords and princes. The British enquiry commission of 1832 admitted, “The settlement fashioned with great care and deliberation has to our painful knowledge subjected almost the whole of the lower classes to most grievous oppression.” Charles Ball, a historian of the revolt, wrote, “in Bengal an amount of suffering and debasement existed which probably was not equaled and certainly not exceeded, in the slave-sates of America.”

The Players

The Empire’s rule was vicious. Governor-General Lord Dalhousie wrote in 1855,“torture in one shape or other is practised by the lower subordinates in every British province.” The Report of the Commission for the Investigation of Alleged Cases of Torture at Madras, 1855, admitted `the general existence of torture for revenue purposes’. Torture was also normal police practice. The conflict, the cumulative effect of several causes developing for a hundred years, was complex in character. These causes arose largely out of the British policy of westernisation which accelerated markedly in the decade after 1848 during the regime of the Marquess of Dalhousie, the young, authoritarian and impetuous Governor-General. The main causes could be described broadly as political, economic, social, military and geographical in nature. Politically, the most serious issue arose out of the British introduction of the British ‘Doctrine of Lapse.’ This doctrine permitted the British to extend their imperial domain at the expense of Indian princes by forbidding the inheritance of states by persons who were not natural heirs; it was also extended to pensions and princely titles. The result was that several states – Udaipur, Jhansi and Nagpur and, finally in 1856, the state of Oudh – lapsed into British sovereignty. Imperialist, expansionist, the epitome of British rule in India. These are perhaps the most apt adjectives for Lord Dalhousie, appointed Governor General of India in 1848.In his eight years at the helm, James Andrew Broun-Ramsay, 1st Marquess of Dalhousie, better known as Lord Dalhousie, was all that and more. He expanded Britain’s empire in India by fair means and foul and held total sway over the vast realm. He was known for his overbearing self-confidence, centralising activity and reckless annexations.

The Empire’s rule was vicious. Governor-General Lord Dalhousie wrote in 1855,“torture in one shape or other is practised by the lower subordinates in every British province.” The Report of the Commission for the Investigation of Alleged Cases of Torture at Madras, 1855, admitted `the general existence of torture for revenue purposes’. Torture was also normal police practice. The conflict, the cumulative effect of several causes developing for a hundred years, was complex in character. These causes arose largely out of the British policy of westernisation which accelerated markedly in the decade after 1848 during the regime of the Marquess of Dalhousie, the young, authoritarian and impetuous Governor-General. The main causes could be described broadly as political, economic, social, military and geographical in nature. Politically, the most serious issue arose out of the British introduction of the British ‘Doctrine of Lapse.’ This doctrine permitted the British to extend their imperial domain at the expense of Indian princes by forbidding the inheritance of states by persons who were not natural heirs; it was also extended to pensions and princely titles. The result was that several states – Udaipur, Jhansi and Nagpur and, finally in 1856, the state of Oudh – lapsed into British sovereignty. Imperialist, expansionist, the epitome of British rule in India. These are perhaps the most apt adjectives for Lord Dalhousie, appointed Governor General of India in 1848.In his eight years at the helm, James Andrew Broun-Ramsay, 1st Marquess of Dalhousie, better known as Lord Dalhousie, was all that and more. He expanded Britain’s empire in India by fair means and foul and held total sway over the vast realm. He was known for his overbearing self-confidence, centralising activity and reckless annexations.  However, history has also attributed far-reaching reforms to Dalhousie. Among his major reforms were those in the fields of education, public works, post and telegraph. Above all, he will always be remembered for introducing the railways in India. It was during his tenure as Governor General that on April 16, 1853, at 3.35pm, the first train in India left Bombay for Thane. Trains were started the next year in the Calcutta area and work began on the Madras-Arcot line in the South. Lord Dalhousie’s famous Railway Minute of April 20, 1853 laid down the policy that private enterprise would be allowed to build railways in India but that their operation would be closely supervised by the government. He was also responsible for introducing the 5′ 6″ gauge for railways in India and the initial lines all used this gauge. Lord Dalhousie favoured 6′ and 5′-6′ was the compromise agreed to. It was only after the departure of Lord Dalhousie that other gauges were also introduced in the country.

However, history has also attributed far-reaching reforms to Dalhousie. Among his major reforms were those in the fields of education, public works, post and telegraph. Above all, he will always be remembered for introducing the railways in India. It was during his tenure as Governor General that on April 16, 1853, at 3.35pm, the first train in India left Bombay for Thane. Trains were started the next year in the Calcutta area and work began on the Madras-Arcot line in the South. Lord Dalhousie’s famous Railway Minute of April 20, 1853 laid down the policy that private enterprise would be allowed to build railways in India but that their operation would be closely supervised by the government. He was also responsible for introducing the 5′ 6″ gauge for railways in India and the initial lines all used this gauge. Lord Dalhousie favoured 6′ and 5′-6′ was the compromise agreed to. It was only after the departure of Lord Dalhousie that other gauges were also introduced in the country. Rani of Jhansi was largely gifted, possessed great energy and a lady oh high character, much respected by everyone at Jhansi. Under Hindu law she had the right to adopt an heir to her husband when he died childless in 1854. Lord Dalhousie refused to her the exercise that right, and declared that Jhansi had lapsed to the paramount power. In vain did the Rani dwell upon the services which in olden days the rulers of Jhansi had rendered to the British Government. Lord Dalhousie was not to be moved. With the stroke of the pen he deprived this high-spirited woman the rights which she believed, and which all the people of India believed, to be hereditary. That stroke of the pen converted the lady, of so high a character and so much respected, into a veritable tigress so far as the English were concerned. For them, thereafter she would have no mercy. There is reason to believe that she, too, had entered into negotiations with the Maulavi and Nana Saheb before the explosion of 1857 took place.

Rani of Jhansi was largely gifted, possessed great energy and a lady oh high character, much respected by everyone at Jhansi. Under Hindu law she had the right to adopt an heir to her husband when he died childless in 1854. Lord Dalhousie refused to her the exercise that right, and declared that Jhansi had lapsed to the paramount power. In vain did the Rani dwell upon the services which in olden days the rulers of Jhansi had rendered to the British Government. Lord Dalhousie was not to be moved. With the stroke of the pen he deprived this high-spirited woman the rights which she believed, and which all the people of India believed, to be hereditary. That stroke of the pen converted the lady, of so high a character and so much respected, into a veritable tigress so far as the English were concerned. For them, thereafter she would have no mercy. There is reason to believe that she, too, had entered into negotiations with the Maulavi and Nana Saheb before the explosion of 1857 took place. Nana Saheb was the adopted son of the Peshwa Baji Rao. This Peswa had been by virtue of his title, the lord of the Maratha princes. Of all the Peshwas, Baji Rao had been loyal to the British. Tempeted, however in 1817, by the rising of Holkar and the war with the Pindaris, and hoping to recover the lost influence of his house, he had risen, had been defeated, and, in 1818, had thrown himself on the mercy of the British. He was deprived of his dominions, and granted a pension for life of eight lakh of rupees. He took up his residence at Bithor, near the military station of Kanpur, adopted Nana Saheb, and lived a quiet life till his death in 1851. The Government of India permitted his adopted son, whose name was Dhundu Pant, but who was generally known as Nana Saheb, to inherit the savings of Baji Rao, and they presented to him the fee-simple of the property of Bithor. But Nana Saheb had to provide for a very large body of followers, given to his care by Baji Rao, and the two British Commissioners who, in succession, superintended the administration of the estate supported the proposal made from Bithor that a portion of the ex-Peshwas allowance should be reserved for the support of the family. They had some reason for their suggestion, for when, some little time before his death, Baji Rao had petitioned the Home Government that his adopted son might succeed to the title and pension of Peshwa. Lord Dalhousie declared the recommendation made by the two commissioners in his favour to be ‘uncalled for and unreasonable’. He directed that ‘the determination of the Government of India may be explicitly declared to the family without delay’.

Nana Saheb was the adopted son of the Peshwa Baji Rao. This Peswa had been by virtue of his title, the lord of the Maratha princes. Of all the Peshwas, Baji Rao had been loyal to the British. Tempeted, however in 1817, by the rising of Holkar and the war with the Pindaris, and hoping to recover the lost influence of his house, he had risen, had been defeated, and, in 1818, had thrown himself on the mercy of the British. He was deprived of his dominions, and granted a pension for life of eight lakh of rupees. He took up his residence at Bithor, near the military station of Kanpur, adopted Nana Saheb, and lived a quiet life till his death in 1851. The Government of India permitted his adopted son, whose name was Dhundu Pant, but who was generally known as Nana Saheb, to inherit the savings of Baji Rao, and they presented to him the fee-simple of the property of Bithor. But Nana Saheb had to provide for a very large body of followers, given to his care by Baji Rao, and the two British Commissioners who, in succession, superintended the administration of the estate supported the proposal made from Bithor that a portion of the ex-Peshwas allowance should be reserved for the support of the family. They had some reason for their suggestion, for when, some little time before his death, Baji Rao had petitioned the Home Government that his adopted son might succeed to the title and pension of Peshwa. Lord Dalhousie declared the recommendation made by the two commissioners in his favour to be ‘uncalled for and unreasonable’. He directed that ‘the determination of the Government of India may be explicitly declared to the family without delay’.

Nana Saheb appealed to the Court of Directors against the decision of the Governor-General of India. His appeal was couched in logical, temperate and convincing language. He asked why the heir to the Peshwa should be treated differently from other native princes who had fallen before the Company. He instanced the case of Delhi & Mysore. This argument had no effect whatsoever on the minds of the western rulers who governed the country from the Leadenhall Street in England. Their reply emulated in its curtness and its rudeness the answer given by Lord Dalhaousie. They directed the Governor-General to inform the memorialist ‘that the pension of his adoptive father was not hereditary, that he has no claim whatever to it, and his application is wholly inadmissible’. The date of reply was May 1853. It bore its fruits at Kanpur in June 1857.

The players were not wanting to the occasion. There was a large amount of seething discontent in many portions of India. In Oudh, recently annexed; in the terrtories under the the rule of the Lieutenent-Governor of the North-west Provinces, revolutionised by the introduction of the land-tenure system of Mr. Thomason. Suddenly shortly after the annexation of Oudh, this seething discontent found expression. Who all the active participants were may probably never be known. One of them, there can be no question, was he who, during the progress of Mutiny, was known as the Maulavi. The Maulavi was a very remarkable man. His name was Ahmad-Ulla, and he hailed from Faizabad in Oudh. He was tall,lean, and muscualr, with large deep-set eyes,beetle brows, a high aqualine nose and lantern jaws. Sir Thomas Seaton, who enjoyed, during the suppression o the revolt, the best means of judging him, described him ‘as a man of great abilities, of undaunted courage, of stern determination, and by far the best soldier among the rebels.’ Such was the man selected by the discontended in Oudh to sow throughout India the seeds which, on a given signal, should spring to active growth. Very soon after the annexation of Oudh by the British, he travelled over the North-west Provinces on a mission which was a mystery to the European authorities; tahe he stayed sometime at Agra; that he visited Delhi, Mirath, Patna and Calcutta; that , in April 1857, shortly after his return he circulated seditious(according to the British) papers throughout Oudh; that the police did not arrest him that the executive at Lucknow, alarmed at his progress, despatched a body of troops to seize him; that taken prisoner, he was tried and condemned to death; that, before the sentence could be executed, the Mutiny broke out; that escaping, he became the confidential friend of the Begum of Lucknow, the trusted leader of the rebels.

The players were not wanting to the occasion. There was a large amount of seething discontent in many portions of India. In Oudh, recently annexed; in the terrtories under the the rule of the Lieutenent-Governor of the North-west Provinces, revolutionised by the introduction of the land-tenure system of Mr. Thomason. Suddenly shortly after the annexation of Oudh, this seething discontent found expression. Who all the active participants were may probably never be known. One of them, there can be no question, was he who, during the progress of Mutiny, was known as the Maulavi. The Maulavi was a very remarkable man. His name was Ahmad-Ulla, and he hailed from Faizabad in Oudh. He was tall,lean, and muscualr, with large deep-set eyes,beetle brows, a high aqualine nose and lantern jaws. Sir Thomas Seaton, who enjoyed, during the suppression o the revolt, the best means of judging him, described him ‘as a man of great abilities, of undaunted courage, of stern determination, and by far the best soldier among the rebels.’ Such was the man selected by the discontended in Oudh to sow throughout India the seeds which, on a given signal, should spring to active growth. Very soon after the annexation of Oudh by the British, he travelled over the North-west Provinces on a mission which was a mystery to the European authorities; tahe he stayed sometime at Agra; that he visited Delhi, Mirath, Patna and Calcutta; that , in April 1857, shortly after his return he circulated seditious(according to the British) papers throughout Oudh; that the police did not arrest him that the executive at Lucknow, alarmed at his progress, despatched a body of troops to seize him; that taken prisoner, he was tried and condemned to death; that, before the sentence could be executed, the Mutiny broke out; that escaping, he became the confidential friend of the Begum of Lucknow, the trusted leader of the rebels.The Plan

It is possible that, whilst the Maulavi was in Calcutta, he constantly in communication with the Sipahis satationed in the vicinity of that city, discovered the instrument which should act with certain effect on thier already excited natures. It happened that, shortly before, the Government of India had authorised the introduction of the newEnfield Musket in the ranks of the native army with a new cartridge, the exterior of which was smeared with fat.

It is possible that, whilst the Maulavi was in Calcutta, he constantly in communication with the Sipahis satationed in the vicinity of that city, discovered the instrument which should act with certain effect on thier already excited natures. It happened that, shortly before, the Government of India had authorised the introduction of the newEnfield Musket in the ranks of the native army with a new cartridge, the exterior of which was smeared with fat.  These cartridges were prepared in the Goverment factory at Dum-Dum near Calcutta. The practice with old paper cartridges, used with the old musket, the ‘Brown Bess’, had been to bite off the paper at one end previous to ramming it down the barrel. When the players suddenly lighted upon the new cartridge, not only smeared, but smeraed with the fat of the pig or the cow, the one hateful to the Muslims, the other the sacred animal of the Hindus, they recognised that they had found a weapon potent enough to rouse to action the armed men of the races which professed those religions

These cartridges were prepared in the Goverment factory at Dum-Dum near Calcutta. The practice with old paper cartridges, used with the old musket, the ‘Brown Bess’, had been to bite off the paper at one end previous to ramming it down the barrel. When the players suddenly lighted upon the new cartridge, not only smeared, but smeraed with the fat of the pig or the cow, the one hateful to the Muslims, the other the sacred animal of the Hindus, they recognised that they had found a weapon potent enough to rouse to action the armed men of the races which professed those religionsThe Gathering Storm (Barrackpore)

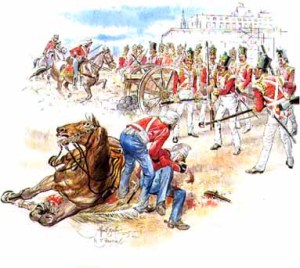

At Barrackpore near Calcutta on the 29th of March, Sunday afternoon, it was reported to Lieutenent Baugh, Adjutant of thr 34th N.I. (Native Infantry), that several men of his regiment were in very excited condition; that one of themMangal Pandey by name, was striding up and down in front of the lines of the regiment, armed with a loaded musket, calling upon the men to rise, and threatening to shoot the first European he should see. Baugh at once buckled on his sword, and putting loaded pistol in his holsters, mounted his horse, and galloped down to the lines. Mangal Pandey heard the sound of the galloping horse, and taking post behind the station gun, which was in fron of the quarter-guard of the 34th, took a deliberate aim at Baugh, and fired. He missed Baugh, but the bullet struck his horse in the flank, and horse and rider were brought to the ground. Baugh quickly disentangled himself, and, seizing one of his pistols, advanced towards the mutinous sipahi and fired. He missed. Before he could draw his sword Mangal Pandey, armed with a talwar with which he had provided himself, closed with the adjutant, and, being the stronger man, brought him to the ground. He would probably have despatched him but for the timely intervention of Muhammadan sipahi, Shaik Paltu by name.

At Barrackpore near Calcutta on the 29th of March, Sunday afternoon, it was reported to Lieutenent Baugh, Adjutant of thr 34th N.I. (Native Infantry), that several men of his regiment were in very excited condition; that one of themMangal Pandey by name, was striding up and down in front of the lines of the regiment, armed with a loaded musket, calling upon the men to rise, and threatening to shoot the first European he should see. Baugh at once buckled on his sword, and putting loaded pistol in his holsters, mounted his horse, and galloped down to the lines. Mangal Pandey heard the sound of the galloping horse, and taking post behind the station gun, which was in fron of the quarter-guard of the 34th, took a deliberate aim at Baugh, and fired. He missed Baugh, but the bullet struck his horse in the flank, and horse and rider were brought to the ground. Baugh quickly disentangled himself, and, seizing one of his pistols, advanced towards the mutinous sipahi and fired. He missed. Before he could draw his sword Mangal Pandey, armed with a talwar with which he had provided himself, closed with the adjutant, and, being the stronger man, brought him to the ground. He would probably have despatched him but for the timely intervention of Muhammadan sipahi, Shaik Paltu by name.The Outbreak (Meerut)

Sunday, the 10th of May, dawned in peace and happiness. The early morning service, at the Cantoment Church, saw many assembled together, some never to meet on earth again. The day passed in quiet happiness; no thought of danger disturbed the serenity of that happy home. Alas! how differently closed the Sabbath which dawned so tranquilly. We were on the point of going to the evening service, when the disturbance commenced on the Native Parade ground. Shots and volumes of smoke told of what was going on: our servants begged us not to show ourselves, and urged the necessity of closing our doors, as the mob were approaching. Mr. Greathed [her husband], after loading his arms, took me to the terrace on the top of the house; two of our countrywomen also took refuge with us to escape from the bullets of the rebels. Just at this moment, Mr. Gough, of the 3rd Cavalry, galloped full speed up to the house. He had dashed through the mutinous troops, fired at on all sides, to come and give us notice of the danger. The nephew of the Afghan Chieftain, Jan Fishan, also came for the same purpose, and was, I regret to say, wounded by a Sepoy. The increasing tumult, thickening smoke, and fires all around, convinced us of the necessity of making our position as safe as we could; our guard were drawn up below. After dark, a party of insurgents rushed into the grounds, drove off the guard, and broke into the house, and set it on fire. On all sides we could hear them smashing and plundering, and calling loudly for us; it seemed once or twice as though footsteps were on the staircase, but no one came up. We owed much to the fidelity of our servants: had but one proved treacherous, our lives must have been sacrificed…….Elisa Greatehead, wife of the then Commissioner of Meerut Mr. H. Greathed

Sunday, the 10th of May, dawned in peace and happiness. The early morning service, at the Cantoment Church, saw many assembled together, some never to meet on earth again. The day passed in quiet happiness; no thought of danger disturbed the serenity of that happy home. Alas! how differently closed the Sabbath which dawned so tranquilly. We were on the point of going to the evening service, when the disturbance commenced on the Native Parade ground. Shots and volumes of smoke told of what was going on: our servants begged us not to show ourselves, and urged the necessity of closing our doors, as the mob were approaching. Mr. Greathed [her husband], after loading his arms, took me to the terrace on the top of the house; two of our countrywomen also took refuge with us to escape from the bullets of the rebels. Just at this moment, Mr. Gough, of the 3rd Cavalry, galloped full speed up to the house. He had dashed through the mutinous troops, fired at on all sides, to come and give us notice of the danger. The nephew of the Afghan Chieftain, Jan Fishan, also came for the same purpose, and was, I regret to say, wounded by a Sepoy. The increasing tumult, thickening smoke, and fires all around, convinced us of the necessity of making our position as safe as we could; our guard were drawn up below. After dark, a party of insurgents rushed into the grounds, drove off the guard, and broke into the house, and set it on fire. On all sides we could hear them smashing and plundering, and calling loudly for us; it seemed once or twice as though footsteps were on the staircase, but no one came up. We owed much to the fidelity of our servants: had but one proved treacherous, our lives must have been sacrificed…….Elisa Greatehead, wife of the then Commissioner of Meerut Mr. H. GreathedCawnpore (Kanpur)

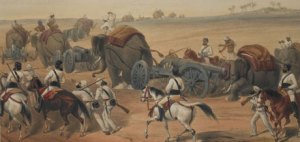

In June 1857 the British garrison at Cawnpore (Kanpur) was besieged by mutineers led by Nana Sahib who fooled the Cawnpore commander, General Sir Hugh Wheeler into letting his guards in to protect the treasury. The sepoys rebelled, looted the treasury and laid siege to the garrison. For nearly three weeks the British hoped for a relief column from Lucknow. Nana Sahib is said to have heard that Sir Henry Havelock’s rescue brigade was approaching and on 25 June offered the garrison safe passage down the Ganges to Allahabad. The British survivors boarded waiting boats and were then trecherously fired upon. Indian cavalrymen rode among the wounded and hacked them to death at Satichaura Ghat. One boat escaped with just four men.

In June 1857 the British garrison at Cawnpore (Kanpur) was besieged by mutineers led by Nana Sahib who fooled the Cawnpore commander, General Sir Hugh Wheeler into letting his guards in to protect the treasury. The sepoys rebelled, looted the treasury and laid siege to the garrison. For nearly three weeks the British hoped for a relief column from Lucknow. Nana Sahib is said to have heard that Sir Henry Havelock’s rescue brigade was approaching and on 25 June offered the garrison safe passage down the Ganges to Allahabad. The British survivors boarded waiting boats and were then trecherously fired upon. Indian cavalrymen rode among the wounded and hacked them to death at Satichaura Ghat. One boat escaped with just four men.Massacre at Bibighar (Cawnpore)

The surviving women and children were imprisoned in a former house of a British officer’s mistress known as the ‘Bibighar’. Here, in two rooms 20 feet by 10, without furniture or straw for bedding, the captives awaited their fate. Responsible for their captivity was member of the Nana’s household, Hosainee Khanum – a former prostitute’s maid nicknamed ‘the Begum’. On 15 July they were all murdered. Their bodies were dumped in a nearby well. The sepoys were were ordered to proceed to the the Bibighar and shoot the women and children. They refused – the women of the Nana’s household had also protested at the order, refusing food and threatening to throw themselves off the rooftops. The guard, threatened with being blown away from guns, marched down to the house, and pointing their muskets through windows, fired into the ceiling. It was then the Begum took a hand. Summoning a member of the Nana’s Maratha guard – reputedly her lover – two Muslim buthchers and two other townsmen, she brought them to the house to do what the sepoys had refused to do. What followed after they enterd the house, was witnessed by an Eurasian drummer named Fitchett, of the 6th Native Infantry,who was interviewed by British officials some months later.

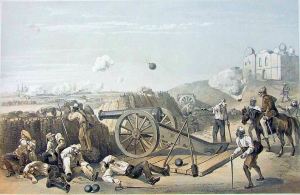

“I heard fearful shrieks. This lasted half an hour or more. I did not see any of the women or children try to escape. A Velatiee (foreigner – in this case Afgan), a stout, short man, and fair, soon came out with sword broken. I saw him go into Nana’s house and bring back another sword. This he also broke in a few minutes, and got a third from the Nana….the groans lasted all night….At about 8 o’clock next morning the sweepers living in the compound, I think there were three or four, were ordered to throw the bodies into a dry well, near the house. The bodies were dragged out, most of them by the hair of the head, those whose clothes were worth taking were stripped. Some of the women were alive, I cannot say how many, but three could speak; they prayed for the sake of God that an end might be put to their sufferings. I remarked one very stout woman, a half-caste, who was severly wounded in both arms, who entreated to be killed. She and two or three others were placed against the bank of the cut by which bullocks go down in drawing water from the well. The dead bodies were first thrown down. Application was made to the Nana about those who were alive. Three children were were also alive. I do not know what order came, but I saw one of the children thrown alive. I believe the other children and women, who were alive were thrown in…… There was a great crowd looking on; they were standing along the walls of the compound. They were principally city people and villagers. Yes, there were also sepoys….They were fair children, the eldest I think must have been six or seven, and the yougest five years; it was the youngest who was thrown in by one of the sweepers. The children were running around the well, where else could they go to? and there was none to save them. No, no one said a word“. The massacre at Cawnpore was to have a profound effect on the British response to the mutiny. All those Indians who were unfortunate enough to be in the path of the British advance would be made to pay a high price regardless of whether they had been involved in the mutiny or not. Those Sepoys who were taken in battle were made to strip and smear their bodies in beef or pork fat before being tied to the front of cannons and blown apart.

There was a great crowd looking on; they were standing along the walls of the compound. They were principally city people and villagers. Yes, there were also sepoys….They were fair children, the eldest I think must have been six or seven, and the yougest five years; it was the youngest who was thrown in by one of the sweepers. The children were running around the well, where else could they go to? and there was none to save them. No, no one said a word“. The massacre at Cawnpore was to have a profound effect on the British response to the mutiny. All those Indians who were unfortunate enough to be in the path of the British advance would be made to pay a high price regardless of whether they had been involved in the mutiny or not. Those Sepoys who were taken in battle were made to strip and smear their bodies in beef or pork fat before being tied to the front of cannons and blown apart.  Those taken in Cawnpore were made to lick the blood from the walls of the Bibighar House and then hanged. Whenever a British soldier might demur at such treatment of a fellow human being the cry of “Remember Cawnpore” would go up. Trials of any prisoners were arbitrary and brief, and usually resulted in a sentence of death. Those convicted of mutiny were

Those taken in Cawnpore were made to lick the blood from the walls of the Bibighar House and then hanged. Whenever a British soldier might demur at such treatment of a fellow human being the cry of “Remember Cawnpore” would go up. Trials of any prisoners were arbitrary and brief, and usually resulted in a sentence of death. Those convicted of mutiny were  either hanged, or lashed to the muzzles of cannon and blown away. It was a cruel punishment with a religious dimension. By blowing the body to pieces the victim lost all hope of entering paradise. The people of northern India called the long period of reprisals ‘the Devil’s Wind’. There were some British officers and administrators who called for lenience towards the Indian people, and who did not believe the myths about mutilation and atrocity. Unfortunately such men were in a minority.

either hanged, or lashed to the muzzles of cannon and blown away. It was a cruel punishment with a religious dimension. By blowing the body to pieces the victim lost all hope of entering paradise. The people of northern India called the long period of reprisals ‘the Devil’s Wind’. There were some British officers and administrators who called for lenience towards the Indian people, and who did not believe the myths about mutilation and atrocity. Unfortunately such men were in a minority.

There was a great crowd looking on; they were standing along the walls of the compound. They were principally city people and villagers. Yes, there were also sepoys….They were fair children, the eldest I think must have been six or seven, and the yougest five years; it was the youngest who was thrown in by one of the sweepers. The children were running around the well, where else could they go to? and there was none to save them. No, no one said a word“. The massacre at Cawnpore was to have a profound effect on the British response to the mutiny. All those Indians who were unfortunate enough to be in the path of the British advance would be made to pay a high price regardless of whether they had been involved in the mutiny or not. Those Sepoys who were taken in battle were made to strip and smear their bodies in beef or pork fat before being tied to the front of cannons and blown apart.

There was a great crowd looking on; they were standing along the walls of the compound. They were principally city people and villagers. Yes, there were also sepoys….They were fair children, the eldest I think must have been six or seven, and the yougest five years; it was the youngest who was thrown in by one of the sweepers. The children were running around the well, where else could they go to? and there was none to save them. No, no one said a word“. The massacre at Cawnpore was to have a profound effect on the British response to the mutiny. All those Indians who were unfortunate enough to be in the path of the British advance would be made to pay a high price regardless of whether they had been involved in the mutiny or not. Those Sepoys who were taken in battle were made to strip and smear their bodies in beef or pork fat before being tied to the front of cannons and blown apart.  Those taken in Cawnpore were made to lick the blood from the walls of the Bibighar House and then hanged. Whenever a British soldier might demur at such treatment of a fellow human being the cry of “Remember Cawnpore” would go up. Trials of any prisoners were arbitrary and brief, and usually resulted in a sentence of death. Those convicted of mutiny were

Those taken in Cawnpore were made to lick the blood from the walls of the Bibighar House and then hanged. Whenever a British soldier might demur at such treatment of a fellow human being the cry of “Remember Cawnpore” would go up. Trials of any prisoners were arbitrary and brief, and usually resulted in a sentence of death. Those convicted of mutiny were  either hanged, or lashed to the muzzles of cannon and blown away. It was a cruel punishment with a religious dimension. By blowing the body to pieces the victim lost all hope of entering paradise. The people of northern India called the long period of reprisals ‘the Devil’s Wind’. There were some British officers and administrators who called for lenience towards the Indian people, and who did not believe the myths about mutilation and atrocity. Unfortunately such men were in a minority.

either hanged, or lashed to the muzzles of cannon and blown away. It was a cruel punishment with a religious dimension. By blowing the body to pieces the victim lost all hope of entering paradise. The people of northern India called the long period of reprisals ‘the Devil’s Wind’. There were some British officers and administrators who called for lenience towards the Indian people, and who did not believe the myths about mutilation and atrocity. Unfortunately such men were in a minority. The Siege (Lucknow)

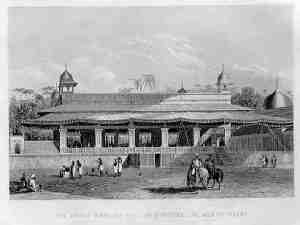

The capital city of Oudh, which had been annexed by the British East India Company in 1856, Lucknow was the home of the British commissioner for the territory. When the initial commissioner proved inept, the veteran administrator Sir Henry Lawrence was appointed to the post. Full-scale rebellion reached Lucknow on May 30 and Lawrence was compelled to use the British 32nd Regiment of Foot to drive the rebels from the city. Improving his defenses, Lawrence conducted a reconnaissance in force to the north on June 30, but was forced back to Lucknow after encountering a well-organized sepoy force at Chinat. Falling back to the Residency, Lawrence’s force of 855 British soldiers, 712 loyal sepoys, 153 civilian volunteers, and 1,280 non-combatants was besieged by the rebels. Comprising around sixty acres, the Residency defenses were centered on six buildings and four entrenched batteries. In preparing the defenses, British engineers had wanted to demolish the large number of palaces, mosques, and administrative buildings that surrounded the Residency, but Lawrence, not wishing to further anger the local populace, ordered them saved.  As a result, they provided covered positions for rebel troops and artillery when attacks began on July 1. The next day Lawrence was mortally wounded by a shell fragment and died on July 4. Command devolved to Colonel Sir John Inglis of the 32nd Foot. Though the rebels possessed around 6,000 men, a lack of unified commandprevented them from overwhelming Inglis’ troops. While Inglis kept the rebels at bay with frequent sorties and counterattacks, Major General Henry Havelock was making plans to relieve Lucknow. Having retaken Cawnpore 48 miles to the south, he intended to press on to Lucknow but lacked the men. Reinforced by Major General Sir James Outram, the two men began advancing on September 18.

As a result, they provided covered positions for rebel troops and artillery when attacks began on July 1. The next day Lawrence was mortally wounded by a shell fragment and died on July 4. Command devolved to Colonel Sir John Inglis of the 32nd Foot. Though the rebels possessed around 6,000 men, a lack of unified commandprevented them from overwhelming Inglis’ troops. While Inglis kept the rebels at bay with frequent sorties and counterattacks, Major General Henry Havelock was making plans to relieve Lucknow. Having retaken Cawnpore 48 miles to the south, he intended to press on to Lucknow but lacked the men. Reinforced by Major General Sir James Outram, the two men began advancing on September 18.

As a result, they provided covered positions for rebel troops and artillery when attacks began on July 1. The next day Lawrence was mortally wounded by a shell fragment and died on July 4. Command devolved to Colonel Sir John Inglis of the 32nd Foot. Though the rebels possessed around 6,000 men, a lack of unified commandprevented them from overwhelming Inglis’ troops. While Inglis kept the rebels at bay with frequent sorties and counterattacks, Major General Henry Havelock was making plans to relieve Lucknow. Having retaken Cawnpore 48 miles to the south, he intended to press on to Lucknow but lacked the men. Reinforced by Major General Sir James Outram, the two men began advancing on September 18.

As a result, they provided covered positions for rebel troops and artillery when attacks began on July 1. The next day Lawrence was mortally wounded by a shell fragment and died on July 4. Command devolved to Colonel Sir John Inglis of the 32nd Foot. Though the rebels possessed around 6,000 men, a lack of unified commandprevented them from overwhelming Inglis’ troops. While Inglis kept the rebels at bay with frequent sorties and counterattacks, Major General Henry Havelock was making plans to relieve Lucknow. Having retaken Cawnpore 48 miles to the south, he intended to press on to Lucknow but lacked the men. Reinforced by Major General Sir James Outram, the two men began advancing on September 18. Due to monsoon rains which had softened the ground, the two commanders were unable to flank the city and were forced to fight through its narrow streets. Advancing on September 25, they took heavy losses in storming a bridge over the Charbagh Canal. Pushing through the city, Outram wished to pause for the night after reaching the Machchhi Bhawan. Desiring to reach the Residency, Havelock lobbied for continuing the attack. This request was granted and the British stormed the final distance to the Residency, taking heavy losses in the process. Making contact with Inglis, the garrison was relieved after 87 days. Though Outram had originally wished to evacuate Lucknow, the large numbers of casualties and non-combatants made this impossible. Rather than retreat in the face of the British success, rebel numbers grew and soon Outram and Havelock were under siege. Despite this, messengers, most notably Thomas H. Kavanagh, were able to reach the Alambagh and a semaphore system soon was established.

Due to monsoon rains which had softened the ground, the two commanders were unable to flank the city and were forced to fight through its narrow streets. Advancing on September 25, they took heavy losses in storming a bridge over the Charbagh Canal. Pushing through the city, Outram wished to pause for the night after reaching the Machchhi Bhawan. Desiring to reach the Residency, Havelock lobbied for continuing the attack. This request was granted and the British stormed the final distance to the Residency, taking heavy losses in the process. Making contact with Inglis, the garrison was relieved after 87 days. Though Outram had originally wished to evacuate Lucknow, the large numbers of casualties and non-combatants made this impossible. Rather than retreat in the face of the British success, rebel numbers grew and soon Outram and Havelock were under siege. Despite this, messengers, most notably Thomas H. Kavanagh, were able to reach the Alambagh and a semaphore system soon was established. While the siege continued, British forces were working to re-establish their control between Delhi and Cawnpore. At Cawnpore, Major General James Hope Grant received orders from the new Commander-in-Chief, Lieutenant General Sir Colin Campbell, to await his arrival before attempting to relieve Lucknow. Reaching Cawnpore on November 3, Campbell moved towards the Alambagh with 3,500 infantry, 600 cavalry, and 42 guns. Outside Lucknow, rebel forces had swelled to between 30,000 and 60,000 men, but still lacked a unified leadership to direct their activities. To tighten their lines, the rebels flooded the Charbagh Canal from the Dilkuska Bridge to the Charbagh Bridge.

While the siege continued, British forces were working to re-establish their control between Delhi and Cawnpore. At Cawnpore, Major General James Hope Grant received orders from the new Commander-in-Chief, Lieutenant General Sir Colin Campbell, to await his arrival before attempting to relieve Lucknow. Reaching Cawnpore on November 3, Campbell moved towards the Alambagh with 3,500 infantry, 600 cavalry, and 42 guns. Outside Lucknow, rebel forces had swelled to between 30,000 and 60,000 men, but still lacked a unified leadership to direct their activities. To tighten their lines, the rebels flooded the Charbagh Canal from the Dilkuska Bridge to the Charbagh Bridge. Campbell planned to attack the city from the east with the goal of crossing the canal near the Gomti River. Moving out on November 15, his men drove rebels from Dilkuska Park and advanced on a school known as La Martiniere. Taking the school by noon, the British repelled rebel counterattacks and paused to allow their supply train to catch up to the advance. The next morning, Campbell found that the canal was dry due to the flooding between the bridges. Crossing, his men fought a bitter battle for the Secundra Bagh and then the Shah Najaf. Moving forward, Campbell made his headquarters in the Shah Najaf around nightfall. With Campbell’s approach, Outram and Havelock opened a gap in their defenses to meet their relief. After Campbell’s men stormed the Moti Mahal, contact was made with Residency and the siege ended. The rebels continued to resist from several nearby positions, but were cleared out by British troops.

Campbell planned to attack the city from the east with the goal of crossing the canal near the Gomti River. Moving out on November 15, his men drove rebels from Dilkuska Park and advanced on a school known as La Martiniere. Taking the school by noon, the British repelled rebel counterattacks and paused to allow their supply train to catch up to the advance. The next morning, Campbell found that the canal was dry due to the flooding between the bridges. Crossing, his men fought a bitter battle for the Secundra Bagh and then the Shah Najaf. Moving forward, Campbell made his headquarters in the Shah Najaf around nightfall. With Campbell’s approach, Outram and Havelock opened a gap in their defenses to meet their relief. After Campbell’s men stormed the Moti Mahal, contact was made with Residency and the siege ended. The rebels continued to resist from several nearby positions, but were cleared out by British troops. The sieges and reliefs of Lucknow cost the British around 2,500 killed, wounded, and missing while rebel losses are not known. Though Outram and Havelock wished to clear the city, Campbell elected to evacuate as other rebel forces were threatening Cawnpore. While British artillery bombarded the nearby Kaisarbagh, the non-combatants were removed to Dilkuska Park and then on to Cawnpore. To hold the area, Outram was left at the easily held Alambagh with 4,000 men. The fighting at Lucknow was seen as a test of British resolve and the final day of the second relief produced more Victoria Cross winners (24)than any other single day. Lucknow was retaken by Campbell the following March.

The sieges and reliefs of Lucknow cost the British around 2,500 killed, wounded, and missing while rebel losses are not known. Though Outram and Havelock wished to clear the city, Campbell elected to evacuate as other rebel forces were threatening Cawnpore. While British artillery bombarded the nearby Kaisarbagh, the non-combatants were removed to Dilkuska Park and then on to Cawnpore. To hold the area, Outram was left at the easily held Alambagh with 4,000 men. The fighting at Lucknow was seen as a test of British resolve and the final day of the second relief produced more Victoria Cross winners (24)than any other single day. Lucknow was retaken by Campbell the following March.The Climax (Delhi)

By 1857, the Mogul dynasty had withered to the point of near extinction. The last of the Moguls, Bahadur Shah II, ‘King of Delhi,’ was a frail, opium-addicted old man deprived of any real power. A pensioner of the British, he was king in name only, and it was understood that upon his death his title would no longer exist. Bahadur Shah’s keepers were British Commissioner Simon Fraser and a Captain Douglas, the commandant of the Palace Guards. Perched on the ridge overlooking Delhi were the British cantonments quartering the 38th, 54th and 74th Native Infantry and one battery of native artillery. By treaty agreement there were no British regiments there. This modest force was commanded by Brig. Gen. Harry Graves. Bahadur Shah was hesitant to accept titular leadership of the uprising. It would mean exchanging a peaceful life that permitted him to write poetry in his luxurious palace for a life promising only risk and turmoil. But he had no choice — he was, in effect, a prisoner of the mutineers. The 3rd Cavalry, now running wild in Delhi, would inevitably be joined by all native units in northern India, he was told.

By 1857, the Mogul dynasty had withered to the point of near extinction. The last of the Moguls, Bahadur Shah II, ‘King of Delhi,’ was a frail, opium-addicted old man deprived of any real power. A pensioner of the British, he was king in name only, and it was understood that upon his death his title would no longer exist. Bahadur Shah’s keepers were British Commissioner Simon Fraser and a Captain Douglas, the commandant of the Palace Guards. Perched on the ridge overlooking Delhi were the British cantonments quartering the 38th, 54th and 74th Native Infantry and one battery of native artillery. By treaty agreement there were no British regiments there. This modest force was commanded by Brig. Gen. Harry Graves. Bahadur Shah was hesitant to accept titular leadership of the uprising. It would mean exchanging a peaceful life that permitted him to write poetry in his luxurious palace for a life promising only risk and turmoil. But he had no choice — he was, in effect, a prisoner of the mutineers. The 3rd Cavalry, now running wild in Delhi, would inevitably be joined by all native units in northern India, he was told. The royal palace housed some 12,000 retainers of one sort or another, who lived a generally unproductive existence. Nevertheless, they spawned countless schemes in the labyrinthine palace corridors to profit from their attachment to the throne. In the early hours of May 11, the king was jarred from his rest when news flashed through the court that the 3rd Native Cavalry from the nearby Meerut cantonment had dashed to Delhi and entered the city by the bridge over the Jumna River. Indeed, Bahadur could hear a cacophony rising from the grounds below his quarters, where the troopers had gathered, demanding an audience. The old king asked Captain Douglas to investigate the disturbance. The 3rd Native Cavalry had left a trail of blood when its troopers broke with the British in a mutinous incident at Meerut and then declared their intention to fight the foreign Raj under the flag of their ‘king.’ Admitted to the palace by sympathizers, the soldiers rampaged through the grounds, killing every Englishman they could find. That attack was only a curtain raiser. Massacres, including the killing of women and children, erupted throughout Delhi.

The royal palace housed some 12,000 retainers of one sort or another, who lived a generally unproductive existence. Nevertheless, they spawned countless schemes in the labyrinthine palace corridors to profit from their attachment to the throne. In the early hours of May 11, the king was jarred from his rest when news flashed through the court that the 3rd Native Cavalry from the nearby Meerut cantonment had dashed to Delhi and entered the city by the bridge over the Jumna River. Indeed, Bahadur could hear a cacophony rising from the grounds below his quarters, where the troopers had gathered, demanding an audience. The old king asked Captain Douglas to investigate the disturbance. The 3rd Native Cavalry had left a trail of blood when its troopers broke with the British in a mutinous incident at Meerut and then declared their intention to fight the foreign Raj under the flag of their ‘king.’ Admitted to the palace by sympathizers, the soldiers rampaged through the grounds, killing every Englishman they could find. That attack was only a curtain raiser. Massacres, including the killing of women and children, erupted throughout Delhi. On the morning of the 11th, as the 3rd Cavalry invested the city, Delhi magistrate Theophilus Metcalf warned Lieutenant George Willoughby, the officer in charge of the main munitions magazine in Delhi, to take all possible steps to keep the magazine from falling into the hands of the mutineers. Willoughby did what he could to make the arsenal defensible, but he knew he did not have the force to fully defend it. With his small staff of British officers, he prepared charges so that he could blow up the arsenal rather than let the mutineers take it, knowing full well that he and his officers would probably be killed by the explosion. The sepoys were not long in laying siege to the arsenal. At 4 p.m., Willoughby gave the order to ignite the vast piles of explosives. A shattering explosion informed the British that Delhi was lost. While the arsenal’s destruction deprived the insurgents of one supply of munitions, another magazine, located three miles outside the city and filled with some 3,000 barrels of gunpowder, had fallen into the hands of the mutineers and would keep them well-supplied. Miraculously, Willoughby and two of his officers had survived the blast and were able to reach British lines.

On the morning of the 11th, as the 3rd Cavalry invested the city, Delhi magistrate Theophilus Metcalf warned Lieutenant George Willoughby, the officer in charge of the main munitions magazine in Delhi, to take all possible steps to keep the magazine from falling into the hands of the mutineers. Willoughby did what he could to make the arsenal defensible, but he knew he did not have the force to fully defend it. With his small staff of British officers, he prepared charges so that he could blow up the arsenal rather than let the mutineers take it, knowing full well that he and his officers would probably be killed by the explosion. The sepoys were not long in laying siege to the arsenal. At 4 p.m., Willoughby gave the order to ignite the vast piles of explosives. A shattering explosion informed the British that Delhi was lost. While the arsenal’s destruction deprived the insurgents of one supply of munitions, another magazine, located three miles outside the city and filled with some 3,000 barrels of gunpowder, had fallen into the hands of the mutineers and would keep them well-supplied. Miraculously, Willoughby and two of his officers had survived the blast and were able to reach British lines. Watching from his command post on the Delhi Ridge, Brigadier Graves could see below him the damage caused by the arsenal’s explosion. But more worrisome than the loss of munitions was the effect the explosion had on the native troops, who were incited to even greater fury. Lieutenant Edward Vibart of the 54th Native Infantry, witness to this tableau of horror, later described it: ‘The horrible truth now flashed on me — we were being massacred right and left, without any means of escape! I made for the ramp which leads from the courtyard to the bastion above….Everyone appeared to be doing the same…the bullets whistled past us like hail. To this day it is a perfect marvel to me how any one of us escaped being hit.’ In searing heat that sometimes reached 140 degrees, the British held off repeated efforts by the mutineers to retake the ridge. Intelligence reports reaching the British suggested a growing schism between Muslim and Hindu mutineers in Delhi. But whatever disputes may have divided the sepoys, retaking a fortified Delhi, whose forces far outnumbered the British, would not be an easy task. Barnard, commanding the ridge force, was reluctant to attack the entrenched positions of the mutineers without further reinforcements, including a proper siege train. June 23, the 100th anniversary of Robert Clive’s victory at the Battle of Plassey, which had marked the completion and consolidation of the British East India Company’s control over India, was a difficult day for the British. On this day, bazaar folklore had it, the British Raj would be driven from the subcontinent. In what may have been an attempt to fulfill that prophecy, the sepoys launched a particularly savage attack on the ridge. The British won the day, however, driving the attackers back to their Delhi ramparts.

Watching from his command post on the Delhi Ridge, Brigadier Graves could see below him the damage caused by the arsenal’s explosion. But more worrisome than the loss of munitions was the effect the explosion had on the native troops, who were incited to even greater fury. Lieutenant Edward Vibart of the 54th Native Infantry, witness to this tableau of horror, later described it: ‘The horrible truth now flashed on me — we were being massacred right and left, without any means of escape! I made for the ramp which leads from the courtyard to the bastion above….Everyone appeared to be doing the same…the bullets whistled past us like hail. To this day it is a perfect marvel to me how any one of us escaped being hit.’ In searing heat that sometimes reached 140 degrees, the British held off repeated efforts by the mutineers to retake the ridge. Intelligence reports reaching the British suggested a growing schism between Muslim and Hindu mutineers in Delhi. But whatever disputes may have divided the sepoys, retaking a fortified Delhi, whose forces far outnumbered the British, would not be an easy task. Barnard, commanding the ridge force, was reluctant to attack the entrenched positions of the mutineers without further reinforcements, including a proper siege train. June 23, the 100th anniversary of Robert Clive’s victory at the Battle of Plassey, which had marked the completion and consolidation of the British East India Company’s control over India, was a difficult day for the British. On this day, bazaar folklore had it, the British Raj would be driven from the subcontinent. In what may have been an attempt to fulfill that prophecy, the sepoys launched a particularly savage attack on the ridge. The British won the day, however, driving the attackers back to their Delhi ramparts.

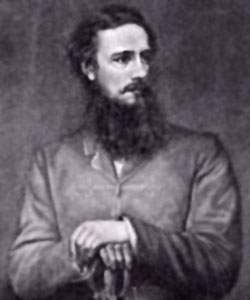

Brigadier General John Nicholson’s flying column, which had dashed down the Grand Trunk high road from the Punjab to Delhi’s relief, arrived to join the British forces on Delhi Ridge in mid-August. The striking-looking, 6 foot 2 inch Irishman had served with distinction for 20 years, and his legendary reputation inspired all who fought under his command. A native cult that revered Nikolsen had even arisen in the Northwest Frontier area and northern Punjab. An admiring lady described his magnetism: ‘He could put his own heart into a whole camp and make believe it was its own.’ Nicholson was so concerned about the state of affairs on Delhi Ridge that, on September 7, he wrote the chief commissioner in the Punjab, Sir John Lawrence, ‘Wilson’s head is going; he says so himself, and it is quite evident he speaks the truth.’ Lawrence then wrote to Wilson, reminding him that the fate of the British throughout India demanded an immediate assault on Delhi. The commissioner understood that if the campaign failed, even the Sikhs would falter in their loyalty. Northwest India would rise, and the tragedy of the First Afghan War would be re-enacted on the flat plains of the Punjab. The eminent Lord Frederick Roberts later reminisced about an extraordinary talk he had with Nicholson during those tense days. The fierce-eyed warrior had said with uncommon conviction: ‘Delhi must be taken and it is absolutely essential that this should be done at once; and if Wilson hesitates longer, I intend to propose at to-day’s meeting that he should be superseded.’

As it turned out, on that day Wilson did order preparations for an assault to begin in earnest. The plan of attack called for General Nicholson to lead a 1,000-man column from the 75th Highlanders to mount the Kashmir Bastion, while another column from the 52nd (Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire) Light Infantry would force the Kashmir Gate, enabling the British troops to fight their way into the city itself. Other columns would breach the Lahore Gate. A total of 5,000 men would take part in the British assault on Delhi.

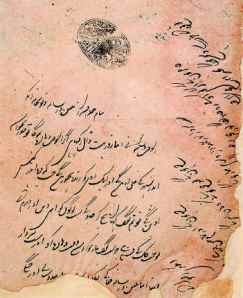

Proclamation by Bakht Khan, the Commander-in-Chief of the rebel army in Delhi. He fears that the English may enter the town and exhorts Hindu and Muslim troops to fight the enemy with zeal. An estimated 30,000 sepoy defenders were now under the command of Bakht Khan, an artillery officer who had 40 years of military experience.

Proclamation by Bakht Khan, the Commander-in-Chief of the rebel army in Delhi. He fears that the English may enter the town and exhorts Hindu and Muslim troops to fight the enemy with zeal. An estimated 30,000 sepoy defenders were now under the command of Bakht Khan, an artillery officer who had 40 years of military experience. The attack was scheduled for 3 a.m. on September 14. ‘There was not much sleep,’ wrote one officer in a letter home that evening. ‘Just after midnight we fell in as quickly as possible, and by the light of a lantern the orders for the assault were read to the men. Any man who might be wounded was to be left where he fell.’ The Roman Catholic Chaplain Bertrand blessed the 75th Highlanders and prayed for mercy ‘on the souls of those soon to die.’

The attack was scheduled for 3 a.m. on September 14. ‘There was not much sleep,’ wrote one officer in a letter home that evening. ‘Just after midnight we fell in as quickly as possible, and by the light of a lantern the orders for the assault were read to the men. Any man who might be wounded was to be left where he fell.’ The Roman Catholic Chaplain Bertrand blessed the 75th Highlanders and prayed for mercy ‘on the souls of those soon to die.’Colonel George Campbell rushed his column to within striking distance of the critical Kashmir Gate and sent a small party of Bengal Engineers, under Lieutenant Duncan Home, to pack explosives under the gate. A firing party of the 52nd covered them as best it could, but the exposed sappers drew terrible fire. Half of them were killed and Lieutenant Philip Salkeld was mortally wounded, but Sergeant John Smith finally managed to touch off the explosion that blew a hole in the gate. As Bugler Robert Hawthorne of the 52nd sounded the attack, the British troops poured through the opening to be met only by the charred corpses of the sepoy defenders. Home, Salkeld, Hawthorne and Smith later received the Victoria Cross for the part they played in blowing open the Kashmir Gate; Salkeld’s was the first VC to be awarded posthumously.

The fight for the city continued in the face of the massed sepoys entrenched beyond the British foothold on the northern extremity of the city. The situation looked hopeless to almost everyone — except Nicholson, who fought for life as he rested near the Kashmir Gate. Now within the city gates, three columns joined forces in an area between the Kashmir Gate and the Anglican church. The fourth column, whose artillery failed to appear amid the confusion, had been forced to retreat beyond the field of fire due to heavy casualties. The troops within the Kashmir Gate had to make their way some 250 yards down a 10-foot-wide lane flanked by flat-topped buildings, from which sepoys maintained a constant rain of fire. Making matters worse were two artillery pieces at the head of the lane and some 1,000 mutineers waiting to fire on the approaching British from atop the so-called Burn Bastion. The 1st Bengal Fusiliers took the lead in making the dash up the lane toward the Lahore Gate, which had to be opened to admit other British units. Powerless against the sheets of rifle fire from the rooftops, the fusiliers fell back. Nicholson then personally led a new attack on the Lahore Gate. Just as he flourished his saber, however, a mutineer fired on him point-blank from a window. Badly wounded, he mustered the strength to prop himself up on one elbow and once again shouted encouragement to his men, but his troops were unable to force this death trap and had to retire. In six hours, the British had lost 66 officers and 1,104 men.

The fight for the city continued in the face of the massed sepoys entrenched beyond the British foothold on the northern extremity of the city. The situation looked hopeless to almost everyone — except Nicholson, who fought for life as he rested near the Kashmir Gate. Now within the city gates, three columns joined forces in an area between the Kashmir Gate and the Anglican church. The fourth column, whose artillery failed to appear amid the confusion, had been forced to retreat beyond the field of fire due to heavy casualties. The troops within the Kashmir Gate had to make their way some 250 yards down a 10-foot-wide lane flanked by flat-topped buildings, from which sepoys maintained a constant rain of fire. Making matters worse were two artillery pieces at the head of the lane and some 1,000 mutineers waiting to fire on the approaching British from atop the so-called Burn Bastion. The 1st Bengal Fusiliers took the lead in making the dash up the lane toward the Lahore Gate, which had to be opened to admit other British units. Powerless against the sheets of rifle fire from the rooftops, the fusiliers fell back. Nicholson then personally led a new attack on the Lahore Gate. Just as he flourished his saber, however, a mutineer fired on him point-blank from a window. Badly wounded, he mustered the strength to prop himself up on one elbow and once again shouted encouragement to his men, but his troops were unable to force this death trap and had to retire. In six hours, the British had lost 66 officers and 1,104 men. On September 19, the Burn Bastion was taken, and on the following day the Lahore Gate finally fell to the British. As the weary days of fighting continued, news of victories was welcome. News of Nicholson’s ebbing life was not. When the great soldier died, he was widely mourned and has ever since rested securely in the British pantheon of war heroes. The last remaining redoubt of the sepoys was believed to be the king’s palace, but when its gates were blown open, it was found to be nearly deserted. At dawn on September 21, a royal salute told all within hearing distance that Delhi had been taken by the Army of Retribution. The seat of the once-great Mogul Empire was forever gone.

On September 19, the Burn Bastion was taken, and on the following day the Lahore Gate finally fell to the British. As the weary days of fighting continued, news of victories was welcome. News of Nicholson’s ebbing life was not. When the great soldier died, he was widely mourned and has ever since rested securely in the British pantheon of war heroes. The last remaining redoubt of the sepoys was believed to be the king’s palace, but when its gates were blown open, it was found to be nearly deserted. At dawn on September 21, a royal salute told all within hearing distance that Delhi had been taken by the Army of Retribution. The seat of the once-great Mogul Empire was forever gone. Bahadur Shah, disillusioned and tired of being manipulated by the sepoys, had hidden a few miles north of the city in Emperor Homayun’s tomb. This was discovered by the intrepid but headstrong Major William Hodson, who was famous along the Northwest Frontier as the leader of hard-riding irregulars known as Hodson’s Horse and who now managed intelligence for the British at Delhi. With 50 of his men he set out on September 21 to bring in the errant king. Bahadur Shah had huddled inside the cloisters of the tomb while thousands of his servants and well-wishers sullenly watched the approaching British horsemen. The king knew that resistance on his part would be pointless, and he accepted Hodson’s promise that the major would spare his life if he gave up quietly.

Bahadur Shah, disillusioned and tired of being manipulated by the sepoys, had hidden a few miles north of the city in Emperor Homayun’s tomb. This was discovered by the intrepid but headstrong Major William Hodson, who was famous along the Northwest Frontier as the leader of hard-riding irregulars known as Hodson’s Horse and who now managed intelligence for the British at Delhi. With 50 of his men he set out on September 21 to bring in the errant king. Bahadur Shah had huddled inside the cloisters of the tomb while thousands of his servants and well-wishers sullenly watched the approaching British horsemen. The king knew that resistance on his part would be pointless, and he accepted Hodson’s promise that the major would spare his life if he gave up quietly.

The British knew that the old Emperor (or “King of Delhi”) was proving to be a focus for the uprising and the mutineers, and that he, his sons and their army were camped just outside Delhi at Humayun’s Tomb; however it was considered too dangerous to assault the enemy force. The General in command said he could not spare a single European. Hodson volunteered to go with 50 of his irregular horsemen, this request was turned down but after some persuasion Hodson obtained from General Wilson permission to ride out to where the enemy were encamped. Hodson rode 6 miles through enemy territory into their camp, containing some 6000+ armed mutineers, a quote from the time says: “His orderly told me that it was wonderful to see the influence which his calm and undaunted look had on the crowd. They seemed perfectly paralysed at the fact of one white man (for they thought nothing of his 50 sowars) carrying off their King alone.”  Here he accepted the surrender of Bahadur Shah II, the last of the Moghul Emperors of India, promising him that his life would be spared.

Here he accepted the surrender of Bahadur Shah II, the last of the Moghul Emperors of India, promising him that his life would be spared.

Here he accepted the surrender of Bahadur Shah II, the last of the Moghul Emperors of India, promising him that his life would be spared.

Here he accepted the surrender of Bahadur Shah II, the last of the Moghul Emperors of India, promising him that his life would be spared.

The capture of the Emperor in the face of a threatening crowd dealt the mutineers a heavy blow. As a sign of surrender the Emperor handed over his arms, which included two magnificent swords, one with the name ‘Nadir Shah’ and the other the seal of Jahangir engraved upon it, which Hodson intended to present to Queen Victoria. The swords he took from the Emperor were given to the Queen as a symbol of the Emperor’s surrender and are still held in the Queen’s Collection.

The princes had refused to surrender and on the following day with one hundred horsemen Hodson went back and demanded the princes’ unconditional surrender. Again a crowd of thousands of mutineers gathered, and Hodson ordered them to disarm, which they did. He sent the princes on with an escort of ten men, while with the remaining ninety he collected the arms of the crowd. On going after the princes, Hodson found the crowd was again pressing towards the escort. The princes were mounted on a bullock-cart and driven towards the city of Delhi. As they approached the city gate, Hodson ordered the three princes to get off the cart and to strip naked. He then shot them dead before stripping the princes of their signet rings, turquoise arm-bands and bejewelled swords. Their bodies were thrown in front of a kotwali, or police-station, and left there to be seen by all. The gate near where they were killed is called the Khooni Darwaza, or Bloody Gate.

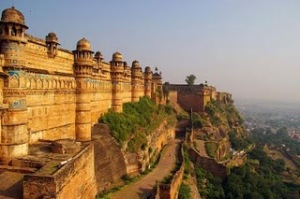

Opposition to British control of Central India centered on the town of Jhansi, where Rani Lakshmi Bai opposed the annexation of her state. In June 1857 the Bengal infantry and cavalry regiments stationed in central India mutinied. The Gwalior Contingent, a force in the service of the pro-British Maharajah Sindia, joined them. On 5 June, British officers, civilians and Indian servants who were sheltering in Jhansi fort, were killed by the Rani’s men. The rebels had offered to spare their lives if they surrendered, and it was believed that the Rani of Jhansi had guaranteed their safety.

Major-General Sir Hugh Rose’s Central India Field Force advanced from Bombay in December 1857. Rose relieved Saugor, where a small European garrison was besieged, on 5 February 1858 and then advanced on Jhansi. The rebels attempted a stand before the city but were defeated at Madanpur. Rose then besieged Jhansi on 24 March before defeating Tantya Tope’s relief army a week later. Tantya Tope was one of Nana Sahib’s men, and was regarded as one of the finest rebel soldiers. On 3 April Jhansi was stormed and looted. At least 5,000 defenders died, but the Rani escaped after personally leading a counter-attack. Rose then advanced on Kalpi and won the battles of Kunch on 1 May and Kalpi itself on 16 May.

The rebels took their remaining forces into Gwalior, hoping to defeat its pro-British ruler. On 1 June at Morar, east of Gwalior, Sindia’s troops changed sides and joined the rebels. Leaving Kalpi on 6 June, Rose marched through the summer heat to Gwalior. He recaptured Morar and then defeated the rebels at Kotah-ke-Serai on 17 June. The Rani was killed in this action. Rose described the Rani as the ‘bravest and the best’ of the rebels. Two days later the British recaptured Gwalior. This effectively ended the rising. Most rebels surrendered or went into hiding, but Tantya Tope managed to avoid the British until April 1859 when he was betrayed, captured and then hanged.

The British claimed that they were bringing civilisation to India, yet they reacted to brutality such as that at Cawnpore with their own savagery and violence. Many innocent people were killed, and looting was rife throughout the army. But at the same time there were great acts of bravery and humanity by Indian people in helping British families to escape from rebels. Often, Indian servants gave their own lives in protecting British children. Soldiers on both sides did what they saw as their duty in defence of their beliefs.

Our own Indian historians feel that the term ‘Indian Mutiny’ is belittling to what they see as a nationalist war. The fact that sepoys rallied around Bahadur Shah as a national symbol adds strength to this argument. The rising was not confined to sepoys, so it was not just a ‘sepoy mutiny’, thousands of ordinary civilians took part.

They were united in wanting to rid India of the British, but they were not looking to unite India. The rising was geographically limited, and when British rule in northern India temporarily collapsed, there was no unified nationalist revolt, but rather a struggle for succession by different local rulers. Other Indian soldiers were crucial in putting down the uprising, so the Indian people cannot be seen as united.

Traditional structures of Indian society began to break down, and there emerged a strong Anglicised and educated colonial-service class with a heightened sense of nationalism. Using modern, ‘western’ methods, such as political parties (chiefly the Indian National Congress), strikes and protest marches, independence was achieved in 1947.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

1.Was the post Bibighar atrocities by the British justified? Well, on hindsight, it appears to be the only way any nation would have responded in a similar situtaion. Emotions do play a big part.

2. Indian nationalist historians have called the sepoy mutiny as the war of independence. In fact it was nationalist Sarvarkar who gave it the name India’s first war of independence. But independence from whom? the Hindoos were already serving under the Mughal rulers!

3. The British defeated the sepoys with help of Sikhs, Gurkhas & Pathans. The English soldiers involved in the war against sepoys were no more than one third of the total British Army.

Search Results

Encyclopaedia of Indian Events & Dates

https://books.google.co.in/books?isbn=8120740742

S. B. Bhattacherje - 2009

He was found guilty of complicity in Sepoy Mutiny and was exiled to Rangoon ... Nana Saheb, alias Dhundu Pant, one of the top leaders of Sepoy Mutiny, died inNana Saheb, alias Dhundu Pant, one of the top l...-- This ...

www.indianage.com/eventdate.php/.../24-September-1859

24-September-1859, Nana Saheb, alias Dhundu Pant, one of the top leaders of Sepoy Mutiny, passed away in Nepal. Our Other Sites MediaWorld.Online Exam - Important Events—24 September 1674 ...

https://www.facebook.com/conquerthenext/posts/520670754682933

1859 – Nana Saheb, alias Dhundu Pant, one of the top leaders of Sepoy Mutiny, passed away in Nepal. 1932 – Preetilata Waddedara, the first armed woman ...Indian Sage Warriors - Facebook

https://www.facebook.com/IndianSageWarriors/posts/222120347953287

24-September-1859 Nana Saheb, alias Dhundu Pant, one of the top leaders of Sepoy Mutiny, passed away in Nepal. 24-September-1931 19 people were killedLeaders of Sepoy Mutiny : India Stamp | iStampGallery.Com

www.istampgallery.com/tatya-tope-nana-saheb-begum-hazrat-mahal-ma...

May 10, 1984 - Leaders of Sepoy Mutiny : India Stamp ... the most intimate friend of the Peshwa's adopted son, Nana Dhundu Pant, known as Nana Saheb.Nana Saheb - Encyclopedia - The Free Dictionary

encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com/Nana+Saheb

b. c.1821, leader in the Indian Mutiny Indian Mutiny, 1857–58, revolt that began with Indian ... It is also known as the Sepoy Rebellion, sepoys being the native soldiers. ..... Click the link for more information. , his real name was Dhundu Pant.[PDF](1) the devil's wind - nana saheb's story - Shodhganga

shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/34336/4/chapter4.pdf

by D Chandra - 2015 - Related articles

The Sepoy Mutiny, as the British called it, or the First War of. Independence, as .... life he was known by two names-Dhondu Pant and Nana Saheb. Malgonkar ...Dr K Prabhakar Rao's blog: MYSTERY OF DISAPPERANCE ...

kuntamukkalaprabhakar.blogspot.com/.../mystery-of-disapperance-of-na...

Mar 6, 2012 - Nana Sahib better known as Dhondupant was the adapted son of exiled last Peshwa Baji Rao II. He played very important role during the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 as ..... had actually been alive till 1926 according to Bajirao alias Suraj Pratap, ... Historians had written that Nana Saheb died in Nepal in 1858, ...The Great Rebellion (1857) | India Explored Blog

https://indiaexplored.wordpress.com/india-1857/

Nana Saheb was the adopted son of the Peshwa Baji Rao. ... whose name wasDhundu Pant, but who was generally known as Nana Saheb, to inherit ..... Indian nationalist historians have called the sepoy mutiny as the war of independence.Full text of "A text-book of Indian history; with geographical ...

archive.org/stream/.../textbookofindian00popeuoft_djvu.txt

In 1299 Alias nephew, Prince Soleiman, made an attempt to imitate his example, and to .... Now also arose that rebellion in Gujarat which led to the establishment of the Bahmant kingdom in the Dakhan. ...... These were the first sepoys in India. ...... He adopted Sirik Dhundu Pant (§ 154), commonly called the Nana Saheb.

No comments:

Post a Comment