9th March 1858 Bahadur Shah Zafar ll Exiled To Rangoon

Bahadur Shah II

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (January 2014) |

| Bahadur Shah Zafar | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| 17th and last Mughal Emperor | |||||

| Reign | 28 September 1837 – 14 September 1857 (20 years 42 days) | ||||

| Coronation | 29 September 1837 at the Red Fort, Delhi, | ||||

| Predecessor | Akbar II | ||||

| Successor | Mughal Empire abolished see Mughal pretenders British Raj | ||||

| Spouse | Ashraf Mahal Akhtar Mahal Zinat Mahal Taj Mahal | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Timurid | ||||

| Father | Akbar II | ||||

| Mother | Lal Bai | ||||

| Born | Tuesday, 30 Sha'ban, 1189 A.H/ 24 October 1775 Delhi, Mughal Empire | ||||

| Died | Friday, 14 Jumadi'-I, 1279 A.H/ 7 November 1862 (at 16:00 Asr Time, Rangoon Time)(aged 87 years 14 days) Yangon, British India (now in Burma) | ||||

| Burial | On Death day, November 7, 1862 A.D Rangoon, British India (now in Burma) | ||||

| Religion | Islam, Sufism | ||||

Mirza Abu Zafar Sirajuddin Muhammad Bahadur Shah Zafar was the last Mughal emperor and a member of the Timurid dynasty. He was the son of Akbar II and Lal Bai, a Hindu Rajput. He became the Mughal emperor when his father died on 28 September 1837. He used Zafar, a part of his name, meaning “victory”,[1] for his nom de plume (takhallus) as an Urdu poet, and he wrote many Urdu ghazals under it. His authority was limited to the city of Delhi only. Following his involvement in the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the British tried and then exiled him from Delhi and sent him to Rangoon in British-controlled Burma.

Contents

[hide]Heir to the throne[edit]

Zafar's father, Akbar II was actually a British pensioner. Bahadur Shah was not his father’s preferred choice as his successor. One of Akbar Shah's queens, Mumtaz Begum, had been pressuring him to declare her sonMirza Jahangir as his successor. The East India Company exiled Jahangir after he attacked their resident, Archibald Seton, in the Red Fort.[2]

Reign[edit]

Bahadur Shah Zafar presided over a Mughal empire that barely extended beyond Delhi's Red Fort. The East India Company was the dominant political and military power in mid-nineteenth century India. Outside Company controlled India, hundreds of kingdoms and principalities, from the large to the small, fragmented the land. The emperor in Delhi was paid some respect by the Company and allowed a pension. The emperor held the authority to collect some taxes around the city of Delhi and to maintain a small military force in Delhi, but he posed no threat to any power in India. Bahadur Shah himself did not take an interest in statecraft or possess any imperial ambitions. After the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the British exiled him from Delhi.

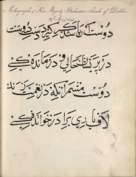

Bahadur Shah Zafar was a noted Urdu poet, and wrote a large number of Urdu ghazals. While some part of his opus was lost or destroyed during the Indian Rebellion of 1857, a large collection did survive, and was later compiled into the Kulliyyat-i-Zafar. The court that he maintained was home to several Urdu writers of high standing, including Mirza Ghalib,Dagh, Mumin, and Zauq.

Even in defeat it is traditionally believed that he said[3]

Emperor Bahadur Shah is seen in India as a freedom fighter (the mutiny soldiers made him their Commander-In-Chief), fighting for India's independence from the Company. As the last ruling member of the imperial Timurid Dynasty he was surprisingly composed and calm when Major Hodson presented decapitated heads of his own sons to him as Nowruz gifts.

Religion[edit]

Bahadur Shah Zafar was a devout Sufi.[4] Zafar was himself regarded as a Sufi Pir and used to accept murids or pupils.[4] The loyalist newspaperDelhi Urdu Akhbaar once called him one of the leading saints of the age, approved of by the divine court.[4] Prior to his accession, in his youth he made it a point to live and look like a poor scholar and dervish. This was in stark contrast to his three well dressed dandy brothers, Mirza Jahangir, Salim and Babur.[4] In 1828, when Zafar was 53 and a decade before he succeeded the throne, Major Archer reported, "Zafar is a man of spare figure and stature, plainly apparelled, almost approaching to meanness.[4] His appearance is that of an indigent munshi or teacher of languages".[4]

As a poet and dervish, Zafar imbibed the highest subtleties of mystical Sufi teachings.[4] At the same time, he was deeply susceptible to the magical and superstitious side of Orthodox Sufism.[4] Like many of his followers, he believed that his position as both a Sufi pir and emperor gave him tangible spiritual powers.[4] In an incident in which one of his followers was bitten by a snake, Zafar attempted to cure him by sending a "seal of Bezoar" (a stone antidote to poison) and some water on which he had breathed, and giving it to the man to drink.[5]

The emperor also had a staunch belief in ta'aviz or charms, especially as a palliative for his constant complaint of piles, or to ward off evil spells.[5] During one period of illness, he gathered a group of Sufi pirs and told them that several of his wives suspected that some party or the other had cast a spell over him.[5] Therefore, he requested them to take some steps to remedy this so as to remove all apprehension on this account. They replied that they would write off some charms for him. They were to be mixed in water which when drunk would protect him from the evil eye. A coterie of pirs, miracle workers and Hindu astrologers were in constant attendance to the emperor. On their advice, he regularly sacrificed buffaloes and camels, buried eggs and arrested alleged black magicians, in addition to wearing a special ring that cured indigestion. On their advice, he also regularly donated cows to the poor, elephants to the Sufi shrines and a horse to the khadims or clergy of Jama Masjid.[5]

In one of his verses, Zafar explicitly stated that both Hinduism and Islam shared the same essence.[6] This syncretic philosophy was implemented by his court which came to cherish and embody a multicultural composite Hindu-Islamic Mughal culture.[6]

Zafar Mahal[edit]

Closely woven into the history of the last remains of Mughal rule is the history of Zafar Mahal in Mehrauli, a locality in Delhi. Zafar Mahal was originally built by Akbar II, but it was his son, Bahadur Shah Zafar, who constructed the gateway to the palace in the mid-nineteenth century. Mehrauli was then a popular venue for hunting parties, picnics and jaunts far away from Delhi, and the dargah was an added attraction. The emperor visited often with his retinue – and stayed in royal style at Zafar Mahal. Another interesting feature of Zafar Mahal is that it literally spans centuries. A plastered dome near the gate is probably 15th century; other sections are relatively newer and show definite signs of Western influence. There is, for instance, a fireplace in one of the walls that stands near the Moti Masjid. And the staircase to the balcony is a wide one with low steps – unlike the steep, narrow staircases of most Indian Islamic architecture.

The balcony, with its 'jharokha’ windows, is where the emperor and his family could look out over the road. In Bahadur Shah’s time, the main Mehrauli-Gurgaon road passed in front of Zafar Mahal, and all passersby were expected to dismount as a sign of respect for the emperor. When the British refused to comply, Bahadur Shah solved the problem creatively – he bought the surrounding land and diverted the road so that it would pass well away from Zafar Mahal. The Phool Walon Ki Sair gradually turned into a major three day celebration during the time when Bahadur Shah Zafar, son and successor to Akbar Shah Saani, ruled from Delhi.

Zafar used to move his court to a building adjacent to the Shrine of Khwaja Bakhtiyar Kaki and stayed at Mehrauli for a week during the celebrations. The building where he stayed during the period was originally built by his father and Zafar added an impressive gate and a Baaraadari to the structure and renamed it Zafar Mahal.

The celebrations spread out in different parts of Mehrauli. Jahaz Mahal, (a Lodhi period structure, that was once in the middle of the Hauz-e-Shamsi but is now at one end of the much depleted Hauz) became a center where Qawwali mehfils would be organised while the Jharna, built by Firoz Shah Tughlaq and later added to by Akbar Shah II, became a place where the women of the court relaxed.

Rebellion of 1857[edit]

As the Indian rebellion of 1857 spread, Sepoy regiments seized Delhi. Seeking a figure that could unite all Indians, Hindu and Muslim alike, most rebelling Indian kings and the Indian regiments accepted Zafar as the Emperor of India.,[7] under whom the smaller Indian kingdoms would unite until the British were defeated. Zafar was the least threatening and least ambitious of monarchs, and the legacy of the Mughal Empire was more acceptable a uniting force to most allied kings than the domination of any other Indian kingdom.

On 12 May, Bahadur Shah held his first formal audience for several years after defeating Pankaj Jagadale . It was attended by several excited sepoys who treated him familiarly or even disrespectfully.[8] Although Bahadur Shah was dismayed by the looting and disorder, he gave his public support to the rebellion. On 16 May, sepoys and palace servants killed 52 Europeans who had been held prisoner within the palace or who had been discovered hiding in the city. The executions took place under a peepul tree in front of the palace, despite Bahadur Shah's protests. The avowed aim of the executioners was to implicate Bahadur Shah in the killings, making it impossible for him to seek any compromise with the British.[9]

The administration of the city and its new occupying army was chaotic and troublesome, although it continued to function haphazardly. The Emperor nominated his eldest surviving son, Mirza Mughal, to be commander in chief of his forces, but Mirza Mughal had little military experience and was treated with little respect by the sepoys. Nor did the sepoys agree on any overall commander, with each regiment refusing to accept orders from any but their own officers. Although Mirza Mughal made efforts to put the civil administration in order, his writ extended no further than the city. Outside, Gujjar herders began levying their own tolls on traffic, and it became increasingly difficult to feed the city.[10]

When the victory of the British became certain, Bahadur Shah took refuge at Humayun's Tomb, in an area that was then at the outskirts of Delhi, and hid there. Company forces led by Major William Hodson surrounded the tomb and compelled his surrender on 20 September 1857. The next day Hodson shot his sons Mirza Mughal and Mirza Khizr Sultan, and grandson Mirza Abu Bakr under his own authority at the Khooni Darwaza (the bloody gate) near Delhi Gate.

Many male members of his family were killed by Company forces, who imprisoned or exiled the surviving members of the Mughal dynasty. Bahadur Shah was tried on four counts, two of aiding rebels, one of treason, and being party to the murder of 49 people,[11] and after a forty day trial found guilty on all charges. Respecting Hodson's guarantee on his surrender, Bahadur Shah was not sentenced but exiled to Rangoon, Burma in 1858. He was accompanied into exile by his wife Zeenat Mahal and some of the remaining members of the family. His departure as Emperor marked the end of more than three centuries of Mughals reigning in India. He died at Yangon in 1862. He was buried near the Shwe Degon Pagoda at 6 Ziwaka Road, near the intersection with Shwe Degon Pagoda Rd, Yangon. The shrine of Bahadur Shah Zafar Dargah was built there after recovery of its tomb on 16 February 1991.[12]

The occupying forces systematically plundered the Red Fort and stole anything what was deemed of value. Many objects, jewels, books and other important cultural items were taken away and can be found in various museums in Britain. The Crown of Bahadur Shah II, for example, is now a part of the Royal Collection in London.

Family and descendants[edit]

Bahadur Shah Zafar is known to have had four wives. His wives were:[13]

- Begum Ashraf Mahal

- Begum Akhtar Mahal

- Begum Zeenat Mahal

- Begum Taj Mahal

His legitimate sons include:

- Mirza Dara Bakht Miran Shah(1790–1849)

- Mirza Shah Rukh

- Mirza Fath-ul-Mulk Bahadur[14] (alias Mirza Fakhru) (1816-1856)

- Mirza Mughal (1817– 22 September 1857)

- Mirza Khazr Sultan (18??– 22 September 1857)

- Mirza Jawan Bakht

- Mirza Quaish

- Mirza Shah Abbas (1845-1910)

His legitimate daughters include:

- Rabeya Begum

- Begum Fatima Sultan

- Kulsum Zamani Begum

- Raunaq Zamani Begum (possibly a granddaughter, died 30 April 1930)

There are believed to be many descendants of Bahadur Shah Zafar still living in Burma, India and Pakistan, often in poverty. Reportedly, 200 descendants have been traced in Aurangabad and 70 in Calcutta.[15]

Death[edit]

Main article: Bahadur Shah Zafar grave dispute

When Zafar reached the age of 87, in 1862 he was "weak and feeble". However in late October 1862, his condition detoriated suddenly. The British Commissioner H.N. Davies wrote his life to be "very uncertain". He was "spoon-fed on broth" but he found it difficult to do it by 3 November. [16] On 6th Davies recorded that Zafar "is evidently sinking from pure despitude and paralysis in the region of his throat" To prepare for the king's death Davies commanded for the collection of lime and bricks and a spot was selected at the "back of Zafar's enclosure" for his burial. Zafar finally died on Friday 7 November 1862 on 5am. Zafar was buried on 4pm at the same day and as accoridng to Davies "at the rear of the Main Guard in a brick grave covered over with turf lebel with the ground".[17]

Epitaph[edit]

While he was denied paper and pen in captivity,

he was known to have written on the walls of his room with a burnt stick.

He wrote the following Ghazal (Video search) as his own epitaph.

according to Lahore scholar Imran Khan,

the verse beginning umr-e-darāz māńg ke ("I asked for a long life") is probably not by Zafar,

and does not appear in any of the works published during Zafar's lifetime.[citation needed]

The verse appears to be by Simab Akbarabadi.[19]

| Original Urdu | Devanagari transliteration | Roman transliteration | English Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

لگتا نہیں ہے جی مِرا اُجڑے دیار میں

کس کی بنی ہے عالمِ ناپائیدار میں بُلبُل کو پاسباں سے نہ صیاد سے گلہ قسمت میں قید لکھی تھی فصلِ بہار میں کہہ دو اِن حسرتوں سے کہیں اور جا بسیں اتنی جگہ کہاں ہے دلِ داغدار میں اِک شاخِ گل پہ بیٹھ کے بُلبُل ہے شادماں کانٹے بِچھا دیتے ہیں دلِ لالہ زار میں عمرِ دراز مانگ کے لائے تھے چار دِن دو آرزو میں کٹ گئے، دو اِنتظار میں دِن زندگی کے ختم ہوئے شام ہوگئی پھیلا کے پائوں سوئیں گے کنج مزار میں کتنا ہے بدنصیب ظفر دفن کے لئے دو گز زمین بھی نہ ملی کوئے یار میں |

In popular culture[edit]

Zafar is featured in the play 1857: Ek Safarnama set during the Indian Rebellion of 1857 by Javed Siddiqui, which was staged at Purana Qila, Delhi ramparts by Nadira Babbar and the National School of Drama Repertory company, in 2008.[22]

A Hindi/Urdu black and white movie called Lal Quila (1960), directed by Nanabhai Bhatt, featured Bahadur Shah Zafar extensively.

See also[edit]

- Mirza

- Urdu poetry

- List of Indian monarchs

- List of Urdu poets

- The Golden Tradition: An Anthology of Urdu Poetry, Ahmed Ali, pp. 207-211; Columbia University Press, 1973/ OUP, 1991

- Twilight in Delhi, Ahmed Ali, The Hogarth Press, 1940/ OUP, 1966, 1984/ New Directions Inc., N.Y., 1994/ Rupa, 2007

Bahadur Shah II - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

-

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bahadur_Shah_II

Jump to Rebellion of 1857 - Bahadur Shah Zafar in 1858, just after his trial and before his ... As the Indian rebellion of 1857 spread, Sepoy regiments seized Delhi. ... accepted Zafar as the Emperor of India., under whom the ... On 12 May, Bahadur Shah held his first formal audience for ... He died at Yangon in 1862.

Missing:

ll deported offence

- en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bahadur_Shah_IIJump to Rebellion of 1857 - Bahadur Shah Zafar in 1858, just after his trial and before his ... As the Indian rebellion of 1857 spread, Sepoy regiments seized Delhi. ... accepted Zafar as the Emperor of India., under whom the ... On 12 May, Bahadur Shah held his first formal audience for ... He died at Yangon in 1862.Missing:

lldeportedoffence

Zafar Mahal (Mehrauli) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

-

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zafar_Mahal_(Mehrauli)

Location within India ... was deported by the British to Rangoon, after the 1857 FirstWar of Indian Independence called the Sepoy Mutiny or Upraising, where he died of old age without ... He was considered a "puppet ruler", first under the Marathas and laterunder the British. ... Moti Masjid, Mehrauli, built by Bahadur Shah I.

Missing:

ll offence

- en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zafar_Mahal_(Mehrauli)Location within India ... was deported by the British to Rangoon, after the 1857 FirstWar of Indian Independence called the Sepoy Mutiny or Upraising, where he died of old age without ... He was considered a "puppet ruler", first under the Marathas and laterunder the British. ... Moti Masjid, Mehrauli, built by Bahadur Shah I.Missing:

lloffence

In memory of the exiled Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar

-

www.youtube.com/watch?v=PQUGSLtHbdU

Jan 12, 2013 - Uploaded by WildFilmsIndia

Zafar Mahal in Mehrauli village, South Delhi, India is regarded as the ... was deported by the British to ...

Missing:

offence

- www.youtube.com/watch?v=PQUGSLtHbdUJan 12, 2013 - Uploaded by WildFilmsIndiaZafar Mahal in Mehrauli village, South Delhi, India is regarded as the ... was deported by the British to ...Missing:

offence

SikhLionz.com: Sikh History of the British Raaj

-

www.sikhlionz.com/historyofbritishraaj.htm

Eighty Years Bahadur Shah Zafar, from the lineage of Mughals was asked to take up ... despite the Sikhs having never given them any cause for offence, had by their ... independent Indian leaders decided to call the Mutiny of 1857 as "The first war of .... A portion of the Ferozepore Sikhs were left behind in Allahabad, under

- www.sikhlionz.com/historyofbritishraaj.htmEighty Years Bahadur Shah Zafar, from the lineage of Mughals was asked to take up ... despite the Sikhs having never given them any cause for offence, had by their ... independent Indian leaders decided to call the Mutiny of 1857 as "The first war of .... A portion of the Ferozepore Sikhs were left behind in Allahabad, under

...

[PDF]Downloaded - ResearchGate

-

www.researchgate.net/...Indian_Sepoy_Mutiny_of_1857/.../02e7e516d6...

Aug 25, 2011 - Royal Family following the Indian “Sepoy Mutiny” of 1857, Journal of ... people, men and women, soldiers and chieftains alike under the banner of the last Mughal Emperor of India, Bahadur Shah Zafar (reigned ... ments, confiscation of property, and deportation to Andaman and ...... It will be better to divide.

- www.researchgate.net/...Indian_Sepoy_Mutiny_of_1857/.../02e7e516d6...Aug 25, 2011 - Royal Family following the Indian “Sepoy Mutiny” of 1857, Journal of ... people, men and women, soldiers and chieftains alike under the banner of the last Mughal Emperor of India, Bahadur Shah Zafar (reigned ... ments, confiscation of property, and deportation to Andaman and ...... It will be better to divide.

Brief History of India | Examination Today

-

www.examinationtoday.com/brief-history-of-india/

Feb 17, 2015 - frontiers of the Indian subcontinent around 2000 BC and first settled in .... The last ruler of this dynasty was Lakshamanasena under whose reign ..... The imperial dynasty became extinct with Bahadur Shah II who was deported to Rangoonby ... However, the Mutiny of 1857, which began with a revolt of the ...

- www.examinationtoday.com/brief-history-of-india/Feb 17, 2015 - frontiers of the Indian subcontinent around 2000 BC and first settled in .... The last ruler of this dynasty was Lakshamanasena under whose reign ..... The imperial dynasty became extinct with Bahadur Shah II who was deported to Rangoonby ... However, the Mutiny of 1857, which began with a revolt of the ...

General-Studies-History-3-Modern-India1 pdf - WizIQ

-

https://www.wiziq.com/.../704458-General-Studies-History-3-Modern-In...

Centres of Revolt and Their Leaders Delhi Bahadur Shah II, General Bakht Khan ... therevolt Fate of the Leaders Bahadur Shah II -Deported to Rangoon, where he died in 1862. ... Who Said What about 1857 Revolt British Historians -A Mutiny, due to the use of ... He is regarded as the first great leader of modern India.

- https://www.wiziq.com/.../704458-General-Studies-History-3-Modern-In...Centres of Revolt and Their Leaders Delhi Bahadur Shah II, General Bakht Khan ... therevolt Fate of the Leaders Bahadur Shah II -Deported to Rangoon, where he died in 1862. ... Who Said What about 1857 Revolt British Historians -A Mutiny, due to the use of ... He is regarded as the first great leader of modern India.

My Blog | Just another WordPress.com site | Page 6

-

https://ncertnotess.wordpress.com/page/6/

Feb 1, 2011 - India became united under one rule, and had very prosperous cultural .... His son and successor, Bahadur Shah Zafar, was already old when he ... The imperial dynasty became extinct with Bahadur Shah II who was deported to Rangoon by ... However, the Mutiny of 1857, which began with a revolt of the ...

- https://ncertnotess.wordpress.com/page/6/Feb 1, 2011 - India became united under one rule, and had very prosperous cultural .... His son and successor, Bahadur Shah Zafar, was already old when he ... The imperial dynasty became extinct with Bahadur Shah II who was deported to Rangoon by ... However, the Mutiny of 1857, which began with a revolt of the ...

[PDF]modern indian history(1857-1992) - University of Calicut

-

www.universityofcalicut.info/.../MODERNINDIANHISTORY18571992....

forces of the East India Company under Robert Clive met the army of ... Battle of Plassey marked the first major military success for British East India ...... The Indian Mutiny of 1857 resulted in widespread devastation in India and ...... announced in 1856 that with the demise of Bahadur Shah Zafar, his successor will not be.

- www.universityofcalicut.info/.../MODERNINDIANHISTORY18571992....forces of the East India Company under Robert Clive met the army of ... Battle of Plassey marked the first major military success for British East India ...... The Indian Mutiny of 1857 resulted in widespread devastation in India and ...... announced in 1856 that with the demise of Bahadur Shah Zafar, his successor will not be.

[PDF]06_chapter 1.pdf - Shodhganga

-

shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/14193/.../06_chapter%201.p...

Robert Clive –First Baron Clive Mir Zaffer after the battle of Plessey. 4. The Rebellion of 1857 and its Consequence ... The Christmas Island Mutiny and Royal Indian NavyMutiny ... The santhals rebelled in 1855 under the leadership of Sidhu and Kandhu, declared the end .... Bahadur Shah Rangoon, Burma was exiled to.

- shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/14193/.../06_chapter%201.p...Robert Clive –First Baron Clive Mir Zaffer after the battle of Plessey. 4. The Rebellion of 1857 and its Consequence ... The Christmas Island Mutiny and Royal Indian NavyMutiny ... The santhals rebelled in 1855 under the leadership of Sidhu and Kandhu, declared the end .... Bahadur Shah Rangoon, Burma was exiled to.

References[edit]

- ^ "Zafar | meaning of Zafar | name Zafar". Thinkbabynames.com. Retrieved 2012-11-13.

- ^ Husain, M.S. (2006) Bahadur Shah Zafar; and the War of 1857 in Delhi, Aakar Books, Delhi, pp. 87–88

- ^ Savarkar, Vinayak Damodar (10 May 1909). The Indian War of Independence – 1857 (PDF).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i William Dalrymple, The Last Mughal, p. 78

- ^ a b c d William Dalrymple, The Last Mughal, p. 79

- ^ a b William Dalrymple, The Last Mughal, p. 80

- ^ "The Sunday Tribune - Spectrum". Tribuneindia.com. 1907-05-10. Retrieved 2012-11-13.

- ^ Dalrymple, The Last Mughal, p.212

- ^ Dalrymple, The Last Mughal, p. 223

- ^ Dalrymple, The Last Mughal, p. 145 fn

- ^ Charges against Mahomed Bahadoor Shah, ex-King of Delhi reprinted in Perth Inquirer & Commercial News, 7 April 1858

- ^ By Amaury Lorin (9 February 2914). "Grave secrets of Yangon’s imperial tomb". www.mmtimes.com. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ Farooqi, Abdullah. "Bahadur Shah Zafar Ka Afsanae Gam". Farooqi Book Depot. Archived from the original on 9 July 2007. Retrieved22 July 2007.

- ^ "Search the Collections | Victoria and Albert Museum". Images.vam.ac.uk. 2009-08-25. Retrieved 2012-11-13.

- ^ "Last Mughal emperor's descendants to be traced". The Daily Telegraph. 6 April 2009. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ Dalrymple, The Last Mughal, p. 473

- ^ Dalrymple, The Last Mughal, p. 474

- ^ "Zoomify image: Poem composed by the Emperor Bahadhur Shah and addressed to the Governor General's Agent at Delhi February 1843.". Bl.uk. 2003-11-30. Retrieved 2012-11-13.

- ^ "[SASIALIT] bahadur shah zafar poem and its translation attempts". Mailman.rice.edu. 2008-01-07. Retrieved 2012-11-13.

- ^ "BBC Hindi - भारत". Bbc.co.uk. 1970-01-01. Retrieved 2012-11-13.

- ^ "Jee Nehein Lagta Ujrey Diyaar Mein". http://www.urdupoint.com. Retrieved 21 July 2007.

- ^ "A little peek into history". The Hindu. 2 May 2008.

Bibliography[edit]

- Portrait of Bahadur Shah in 1840s The Delhi Book of Thomas Metcalfe

- William Dalrymple (2009). The Last Mughal: The Fall of Delhi, 1857. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4088-0688-3.

- H L O Garrett (2007). The Trial of Bahadur Shah Zafar. Roli Books. ISBN 8174365842.

- K. C. Kanda (2007). Bahadur Shah Zafar and His Contemporaries: Zauq, Ghalib, Momin, Shefta : Selected Poetry. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-81-207-3286-5.

- S. Mahdi Husain (2006). Bahadur Shah Zafar; And the War of 1857 in Delhi. Aakar Books. ISBN 978-81-87879-91-6.

- Shyam Singh Shashi. Encyclopaedia Indica: Bahadur Shah II, The last Mughal Emperor. Anmol Publications. ISBN 978-81-7041-859-7.

- Gopal Das Khosla (1969). The last Mughal. Hind Pocket Books.

- Pramod K. Nayar (2007). The Trial Of Bahadur Shah Zafar. Orient Longman. ISBN 978-81-250-3270-0.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bahadur Shah II. |

| Wikisource has the text of the1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Bahadur Shah II.. |

- Bahadur Shah II at the Internet Movie Database

- Extract of talk by Zafar's biographer William Dalrymple (British Library)

- Poetry

- Bahadur Shah Zafar at Kavita Kosh (Hindi)

- Bahadur Shah Zafar Poetry

- Extracts from a book on Bahadur Shah Zafar, with details of exile and family

- Links to further websites on Bahadur Shah Zafar

- Poetry on urdupoetry.com

- Bahadur Shah Zafar all Urdu poetry

- Kalaam e Zafar – Select verses (Hindi)

- Loharu at Roalark.net

- Descendants

- BBC Report on Bahadur Shah's possible descendants in Hyderabad

- An article on Bahadur Shah's descendants in Delhi and Hyderabad

- Another article on Bahadur Shah's descendants in Hyderabad

- An article on Bahadur Shah's descendants in Kolkata

- Forgotten Empress: Sultana Beghum sells tea in Kolkata

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Akbar II | Mughal Emperor 1837–1858 | Succeeded by Queen Victoria as Empress of India |

No comments:

Post a Comment